Article 6 of the Paris Agreement at COP28: What is at stake?

Developing stringent rules for the global carbon market under A6.4 could set a precedent for high standards and restore faith…

The way we produce and consume livestock is fueling the nature and climate crisis. By 2050, if all other economic sectors followed a 1.5C pathway while the meat and dairy industry’s growth continued as usual, the livestock sector could eat up 80% of the remaining GHG budget in 32 years. Experts agree we need to shift diets. “To meet global climate targets, per capita consumption of meat would need to fall drastically,” says Chatham House, but it doesn’t mean meat has to be off the menu for everybody.

Veganuary is a key moment when companies and consumers think more about the personal and wider impacts of the food system. This briefing outlines the reasons we need to rapidly change how we produce animal products, and how eating less and better meat and dairy is one of the best ways for consumers to reduce the impact of their diets on the environment.

Global meat consumption and production is rising across the world. This trend is expected to continue. But, as people become more concerned about the health and environmental impact of their diets, the market for Alternative Protein (AP) products is also growing. In this briefing, AP products are meat and dairy alternatives created to substitute animal products (i.e do not include fruit and vegetables) (see appendix for more stats).

Governments have been subsidising meat and dairy production. For example, nearly 90% of total global farming subsidies (USD 540 bn per year) goes to the production of beef, milk and rice. In the EU, reform of farming subsidies – which account for a third of the EU’s total seven-year budget – is failing to incentivise change towards a more resilient food system. According to OECD, in high-income countries, beef receives the largest subsidies among meats, whereas in middle-income countries, these funds go to poultry, sheep and pork production. However, while many small producers would not be able to survive without this help, a lot of this money is going to support big agribusinesses. The world’s largest banks, investment firms and pension funds have also been big backers of industrialised animal agriculture. Between 2015-20, global meat and dairy companies received over USD 478 bn from over 2,500 investors in the forms of loans, insurance and securities. Two of the world’s leading development banks have pumped billions of dollars into the global livestock sector (USD 2.6 bn) in the past 10 years.

The AP market has received financing mainly from companies and investors. Many venture capital funds are investing in AP companies and research efforts. The global alternative protein companies received USD 3.1 bn in disclosed investments in 2020, which is more than three times as much as the USD 1 bn raised in 2019. Alternative protein companies have raised almost USD 6 bn in capital in the past decade (2010–2020), more than half of which was raised in 2020 alone. Traditional meat producers, newcomers and major food conglomerates (e.g Nestlé and Unilever) are increasingly adding AP alternatives to their product ranges and investing in new companies.

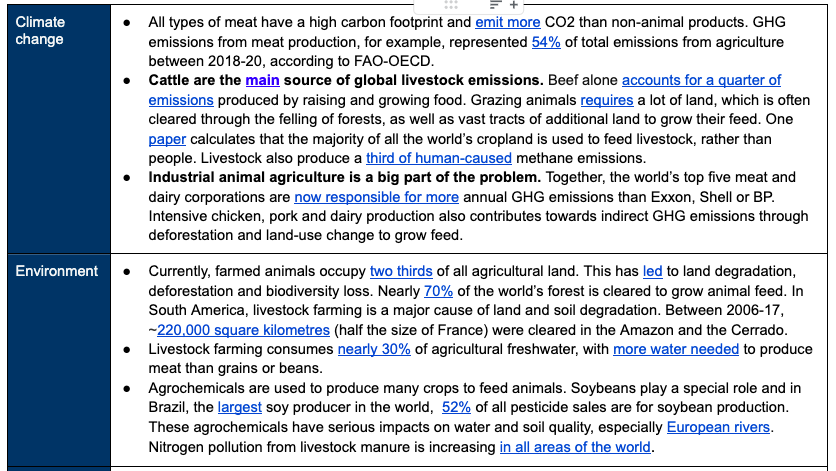

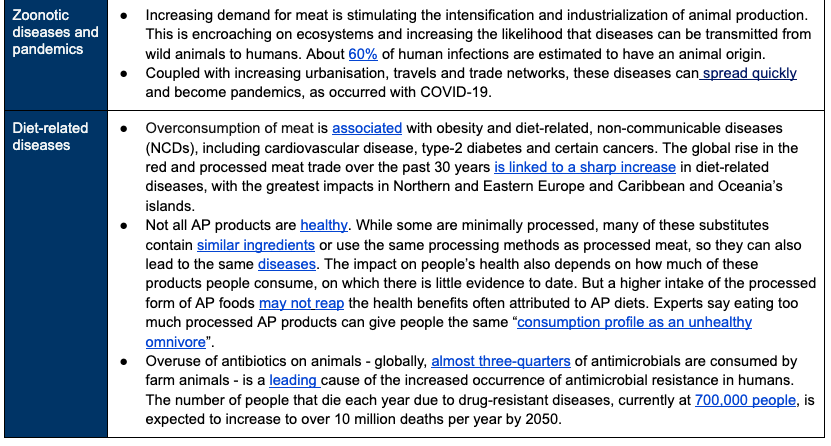

Livestock production and consumption can harm the environment and people’s health. While not all types of production systems lead to negative impacts on the environment – pastoralism in the Sub-Saharan region in Africa helps to conserve biodiversity and sequester carbon, for example – large-scale industrial production contributes to the climate and nature crisis. Over-consuming meat products, especially red and processed meat, is increasing diseases and ill-health in humans. See below for some key stats.

In order to reduce the emissions from our livestock, consumers and producers need to change.

Producers need to adopt land management practices to mitigate the highest impacts of production, as the world is not going to abandon livestock farming completely.[2]There are a number of reasons we wouldn’t want it to – it is not only an important source of income for many, but can also be a key source of nutrition in local settings. Particularly in … Continue reading According to the IPCC, improving livestock and grazing land management as well as including mixing crop-livestock production can help to reduce climate and environmental impacts. Farming systems that shift away from industrial agriculture, such as agroforestry and organic farming, not only help to reduce emissions of all GHG, but also improve farmers’ livelihoods, food security and biodiversity. There are many questions about technological fixes, such as feed additives and anaerobic digesters to reduce methane emissions. These concern their scalability, cost and potential to reduce emissions. Even if they reduce beef’s methane emissions, these emissions would still be higher than those from pork and chicken and AP meats.

Consumers also have a key role to play.Experts agree that a shift to plant-based diets can play a key role in reducing emissions from food systems, which represent up to 37% of global greenhouse emissions . Going vegan can reduce emissions the most (e.g up to 8 GtCO2 eq/yr according to the IPCC).[3]For comparison purposes; in 2010 the whole transport sector produced 7.0 GtCO2-eq of direct GHG emissions. But people don’t need to completely exclude meat from their diets to reduce their dietary footprint. Eating less meat or switching to lower impact meats raised in sustainable systems, such as chicken, could also have a major impact. According to the IPCC, these diets (i.e flexitarian, vegetarian) can reduce emissions between 4.3-6.4 GtCO2 eq/yr by 2050.[4]A flexitarian is a person who eats primarily a vegetarian diet but occasionally eats meat or fish. These diets also tend to be easier for people to adopt, healthier, have smaller land footprints and “present major opportunities for climate adaptation.” People also need to be careful about what they choose to substitute meat with to achieve large global benefits. They should opt for sourcing from farmers that practice regenerative agriculture or other agroecological methods that can support the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss. Reducing consumption in wealthy regions is also necessary to allow people across Asia and Africa to reach their nutritional goals while keeping consumption within planetary boundaries.

Governments can support diet shifts through their own food procurement practices and policies that shape consumption (e.g. dietary guidelines and trade, food and agricultural policies). They can recommend lowering red meat consumption, promote research on alternative proteins or introduce fiscal policies to shift consumption patterns. Several European countries are investing in research on alternative proteins and changing dietary guidelines focusing on reducing consumption of meat. Policy reforms will have a greater impact if governments provide support and incentives for farmers to move away from industrial agriculture, such as redirecting public spending support and encouraging farming that produces meat in ways that benefit the environment, human health and animal welfare. At the same time, policy reforms provide a fair return for farmers and support consumers on lower incomes to access healthy and sustainable diets. However, in reality, most governments are failing to take action. For example, most of the current climate targets (NDCs) pay insufficient attention to agriculture, land-use emissions and food systems. Politicians are also afraid of conflict with farming groups and want to avoid a public backlash against policies that interfere in people’s daily lives, such as meat taxes. They also are failing to include sustainability in their dietary guidelines.

Businesses, restaurants and supermarkets can optimise the pricing and improve marketing of AP foods and dishes, while stopping promoting and discounting meat products. They can also continue to invest in development of AP products and increase efforts to reduce emissions from their supply chain. Several food companies, meatpackets and major retailers, for example, have set net zero targets, which include support for regenerative agriculture, carbon labelling or targets to increase sales of meat alternatives. But most of these net zero target are meaningless. For example, most of the top 35 global meat and dairy giants and top retailers either do not report or underreport their emissions. Also, none of the net zero commitments made by major meat and dairy companies call for reducing the number of animals in their supply chains.

References

| ↑1 | Ultra-processed products usually have many added ingredients such as sugar, salt, fat, artificial colours, preservatives, flavours or stabilisers. Examples of these foods are frozen meals, soft drinks, hot dogs and cold cuts, fast food, packaged cookies, cakes, and salty snacks. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | There are a number of reasons we wouldn’t want it to – it is not only an important source of income for many, but can also be a key source of nutrition in local settings. Particularly in lower-income countries where diets lack diversity, small amounts of meat and dairy can be an essential source of protein and micronutrients. |

| ↑3 | For comparison purposes; in 2010 the whole transport sector produced 7.0 GtCO2-eq of direct GHG emissions. |

| ↑4 | A flexitarian is a person who eats primarily a vegetarian diet but occasionally eats meat or fish. |

Developing stringent rules for the global carbon market under A6.4 could set a precedent for high standards and restore faith…

A handful of countries are setting up 'nature markets' for trading biodiversity offsets, but the concept could lead to greater…