Zero-carbon electricity: powering grids with wind and solar

Electricity grids are the backbone of global energy systems and are becoming increasingly important in the effort to limit global…

Globally, oil and gas companies are facing a significant decline in exploration and production, with serious ramifications for the UK’s North Sea oil and gas industry. Recently, BP wrote down USD 17.5 billion of its assets by trimming its long-term oil and gas price forecast, and warned that it will be laying off about 15% of its workforce.

The UK’s main oil and gas trade body, OGUK, warned on 28 April that 30,000 jobs are expected to be lost in the industry as a result of the oil price shock and the slump in demand triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. But job losses have in fact been quicker than expected, with 4,000 jobs already lost by 15 June, and projections suggesting a quarter of all UK oil workers may lose their jobs. Peak oil demand may have been pushed forward by as much as three years due to COVID-19, according to several analysts as well as oil giants Shell and BP.

As this reality hits a UK already suffering from climbing unemployment – between March and May the number of people claiming unemployment benefits shot up by 126% – it is crucial that the government invests in long-term, sustainable industries and jobs. Channeling funds into an already declining fossil fuel industry will bring no long-term benefits for workers, the economy or the climate.

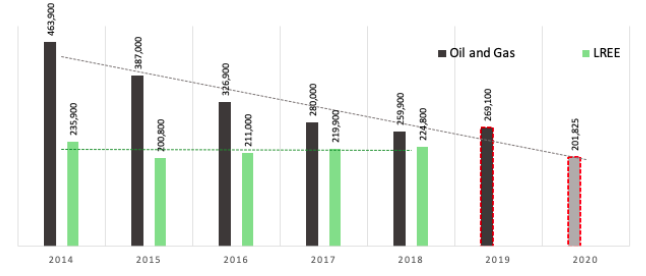

There has been a gradual increase in jobs in the UK’s low-carbon industry since 2015, while fossil fuel jobs in the UK have been consistently decreasing:

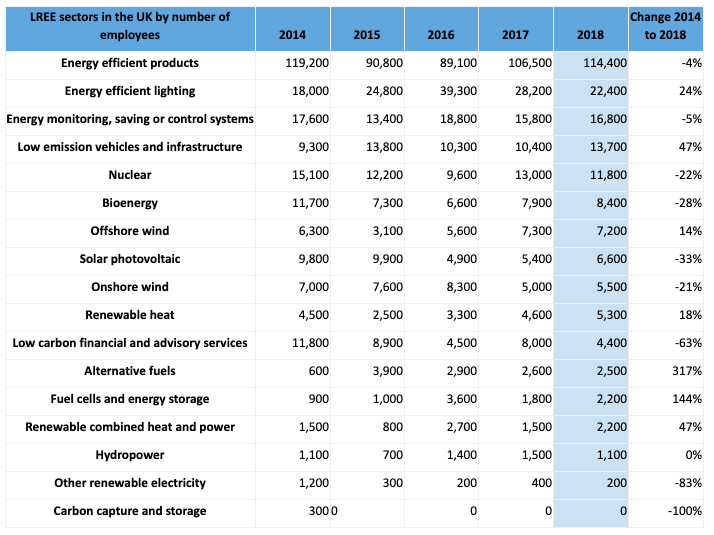

The value of the low-carbon economy increased by 48% between 2015 and 2018 to stand at GBP 8.1 billion. The increase was mainly due to a rise in acquisitions by the offshore wind sector. According to the Office for National Statistics:

Source: Data taken from the Office for National Statistics: Low carbon and renewable energy economy, UK: 2018

Employment in the UK’s offshore oil and gas industry fell by nearly 40% between 2014 and 2018.

Source: Data taken from the Office for National Statistics: 'Low carbon and renewable energy economy, UK: 2018' and Oil and Gas UK’s ‘Workforce report 2019’. Red dashes indicate predicted estimates.

The number of jobs in the UK’s low-carbon industry will have to increase if the government is to meet its binding climate targets of net-zero by 2050.

With the right government support, and following the scenarios laid out by the Committee on Climate Change’s (CCC) core recommendations and National Grid’s Future Energy Scenario, the UK could create 700,000 new green jobs by 2030 and a further 488,000 through to 2050, according to new research by the Local Government Association (LGA).

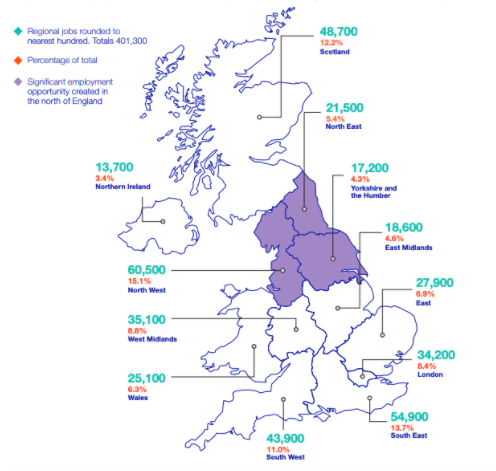

Source: National Grid report Building the net zero energy workforce, 2020.

More jobs will be created if the UK government invests in the low-carbon economy, verus oil and gas.

The fossil fuel sector was already on the cusp of a structural change before the COVID-19 crisis and the UK’s North Sea oil and gas industry was already struggling.

The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) projected in March 2019 that revenues from oil and gas would remain less than 0.1% of the UK’s GDP, after revenues fell by 90% from 2008-2009, when they accounted for 0.7% of GDP.

Transitions from oil and gas that benefit workers and local economies are possible and have been initiated in several geographies around the world. Below are two case studies:

| Inclusive transition from offshore oil and gas, Taranaki, New Zealand, 2019- The Taranaki region is located on the west coast of New Zealand’s North Island. It is fringed by the Tasman Sea and is home to more than 100,000 people. The region is also the centre of the country’s oil and gas industry. In 2018, New Zealand announced that it would end any new licences for offshore exploration, jeopardising jobs in the region at the time when the energy industry represented 28% of the region’s economic output. In response, the government announced the Just Transition Unit to support New Zealand’s transition to a low-emission economy. Transitioning to a clean, green and carbon neutral New Zealand is a key outcome of the government’s strategy for a more productive, sustainable and inclusive economy, with the first region of focus being Taranaki. To this end, the government set up a USD 17 million clean energy centre for the region granting USD 12.7 million for research and development and employing 45 people directly. The transition aims to be as inclusive and participatory as possible, with the government committed to working directly with five central society ‘pillars’: workers, business, central government, local government and indigenous people. During February to April 2019, a roadmap for 2050 was created through a large-scale co-design process. In total, more than 700 people took part in the process through 28 workshops. This case study shows how participatory processes can lead to plans that include and account for local workers. The roadmap launched in May 2019 and was presented by consultants in over 40 locations. A programme of work is now being developed to decide on next steps (in the long and short-term) and to achieve the region’s low emissions vision by 2050. |

| Preparing for coal phase-out and power sector transformation in Germany, 2018- To align with the country’s climate targets, Germany launched a Commission for Just Transitions in 2018. The goal of the commission was to ensure a just transition for industry workers while maintaining Germany’s CO2 emissions reduction targets, and to set a final date for the complete phase-out of coal. Over a period of seven months, the commission discussed how to transition away from coal, while ensuring a just transition for the mining sector and in areas where coal power plants are located. The processes involved expert hearings from a broad range of involved parties, including representatives from affected industry sectors, regions and employees. A 278 page report was accepted nearly unanimously at the end of the negotiation period, with support from all stakeholders and the political sphere. Three union organisations were at the table – The German Trade Union Confederation, and two stakeholders unions, The Industrial Workers’ Union for Mining, Energy and Chemistry, and the United Services Trade Union. The final outcome was a clear pathway, outlining timelines and measures to ensure that workers’ rights are respected and central to the phasing out and reshaping of the conventional power industry. It included a goal of complete coal phase-out by 2038 (with the option of 2035), to create as many decent jobs as those that will be phased out, and the provision of structural aid of EUR 2 billion each year over the next 20 years. |

Electricity grids are the backbone of global energy systems and are becoming increasingly important in the effort to limit global…

Greenwashing can take various forms, such as false advertising or misleading labelling. This guide shows how to spot greenwashing in…