Bullish Asian gas demand forecasts eroded by renewable surge

Increased momentum in the energy transition has led the IEA to reduce its gas demand forecast for 2040 by 1,500…

The success of global climate goals hinges on the ability to decarbonise the oil and gas sector, which accounts for about 42% of global emissions. These companies claim they are taking action, but is this really the case? To separate fact from fantasy, this briefing looks into how the majors aim to reduce emissions, how their net-zero goals will impact their existing fossil fuel portfolios and into which ‘low carbon’ sectors they are moving to diversify their business. This briefing is an update of an earlier briefing written in 2020.

Net-zero fever has gripped the oil and gas sector. In December 2019, almost five years after the Paris Agreement was signed, Repsol issued the first net-zero target in the industry. The bug spread fast. By May 2021, no fewer than 18 integrated oil and gas majors (oil majors) had released targets, while all major European oil majors have now updated their initial net-zero strategies.

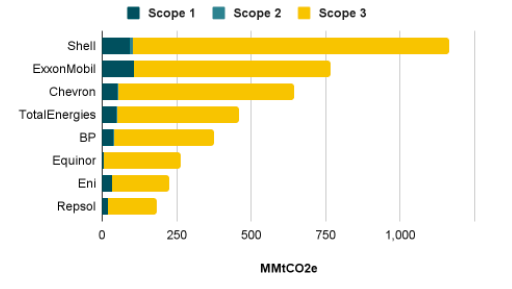

These targets are a welcome development given the scale of the industry’s emissions. The eight largest western oil majors by revenue are jointly responsible for over four gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) each year – over 10% of global emissions (see Figure 1). Shell alone emits over 1 GtCO2e annually. The six European oil majors that have committed to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 have cumulative emissions equal to 2.6 GtCO2e.

Source: Company reports

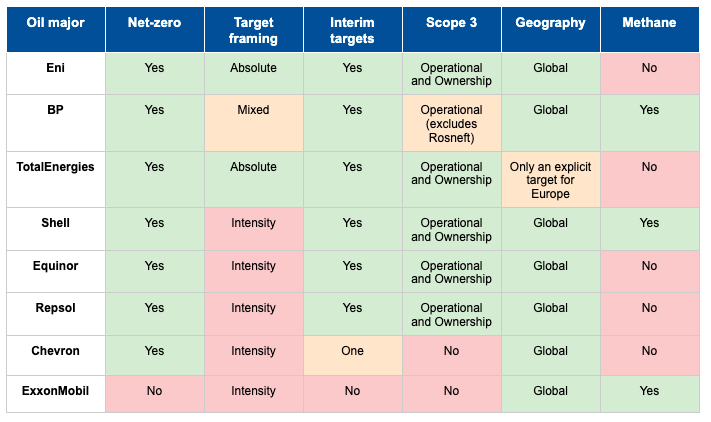

When assessing a company’s net-zero target, there are four key components to consider (see appendix I for more detail):

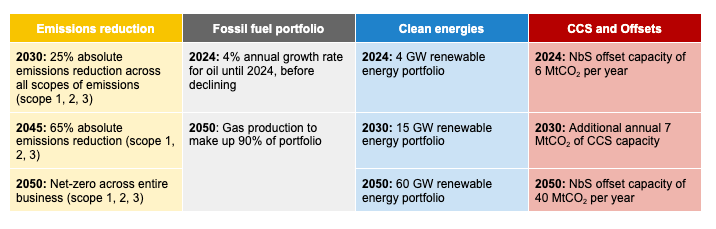

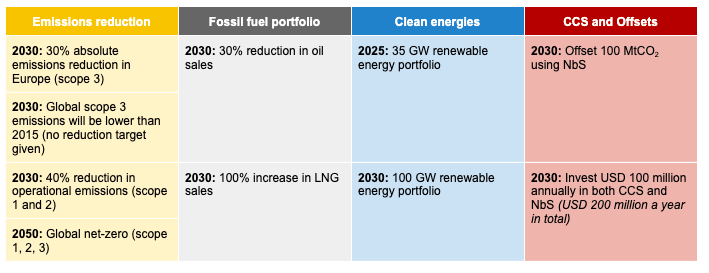

Based on these criteria, only one oil major has set targets that will meaningfully reduce emissions. Italy’s Eni has set numerous targets between now and 2050 (see Table 1) – it aims to reduce its emissions in absolute terms by 25% by 2030 and 65% by 2045, before reaching net-zero in 2050. These targets cover its entire value chain and all three scopes of emission (see appendix I). Including scope 3 – emissions from the use of end products – is particularly important as it covers, on average, 85% of the total emissions of an oil major (89% in the case of the European majors). In addition, Eni’s interim targets are vital as they act as yardsticks against which the company’s progress can be measured. Net-zero goals without interim targets are not credible.

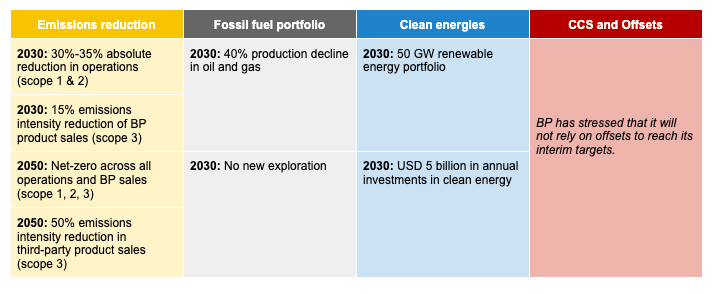

Other majors, like BP and TotalEnergies, have set absolute targets, but in a limited capacity. BP only has absolute reduction targets for scope 1 and 2 – its operational emissions, which represent 12% of its total emissions footprint – and notably excludes its partnership with Rosneft, which accounts for over 30% of its production volumes. Meanwhile, TotalEnergies has set a 30% reduction target in scope 3 emissions, but only in Europe, where 60% of these emissions are generated.

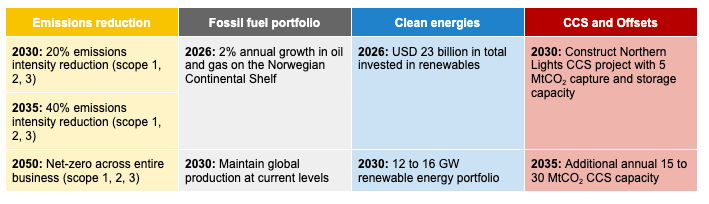

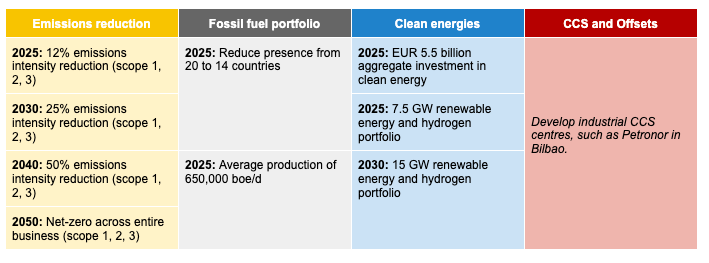

By contrast, Shell, Equinor and Repsol only strive to reduce the intensity of their emissions. These targets aim to reduce emissions per unit of energy produced, rather than cutting total emissions. As such, their targets do not necessarily result in emissions reductions (for example if they produce more energy, total emissions could actually rise). A landmark ruling by a Dutch court, which ordered Shell to target a 45% reduction in emissions by 2030, clearly underscored the fact that its targets fall short.

With two exceptions, all these targets focus solely on reducing CO2 emissions, but tackling methane emissions is an increasingly important component of net-zero strategies. This is particularly true for the oil majors with large gas operations. Though its total emissions are far smaller than CO2, methane is a more potent heat-trapping gas. Additionally, it stays in the atmosphere for a much shorter period of time – decades as opposed to centuries. Therefore, reducing the amount of methane pumped into the atmosphere will have an outsized effect on limiting warming.

Curbing methane emissions is also relatively easy to accomplish, as most emissions occur in the extraction, production and transportation of oil and gas. Existing technologies can already reduce methane leaks across the downstream value chain by 75%, the IEA estimates. Despite this, only BP and Shell make any mention of methane in their targets – both talk of limiting the methane intensity of their fossil fuel products to 0.20%. Methane intensity varies significantly across the industry – in the US, BP’s is 0.75%, Exxon’s is 0.58% and Shell’s is 0.1%, BNEF estimates. Although Shell’s US assets have low methane intensity, some of its global assets have a rating of 0.6%.

Sources: Company disclosures, Carbon Tracker

To meet their emission targets, the oil majors need to curb production. For the world to hit net-zero by 2050, no more oil and gas assets can come online, according to the IEA’s Net-Zero Emissions 2050 scenario. To align with this net-zero trajectory, the output volumes of the European oil majors will have to fall on average by 50% relative to 2021 by the end of the decade, according to Carbon Tracker modelling.

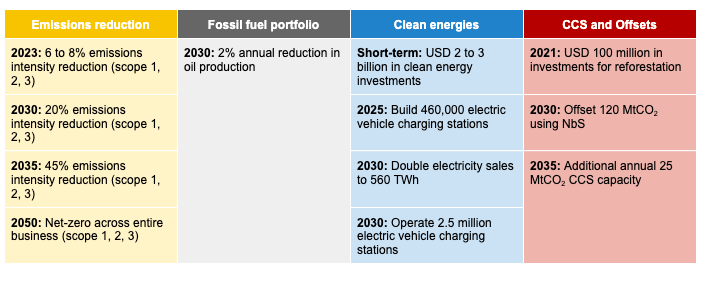

Notionally, this is reflected in net-zero strategies, as some oil majors have committed to limiting production. But they do so at a far slower rate than either the IEA or Carbon Tracker recommends, suggesting that, by the end of this decade, they will be way off track in meeting their net-zero targets. By 2030, BP is pledging to reduce oil and gas production by 40% and TotalEnergies is targeting a 30% reduction in oil product sales. Meanwhile, Shell has said it will curb production by 2% annually through to 2030

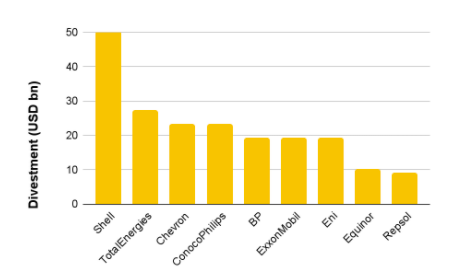

To this end, US and European oil majors divested a combined USD 198 billion between 2015 and 2020, according to BNEF analysis (see Figure 2). Shell leads the pack, with USD 50 billion, followed by TotalEnergies at USD 27 billion. In Shell’s case, the USD 10 billion in divestment a year (2015-2020) is equal to about half its total planned annual investments between now and 2025.

Divestment is being used in two ways. On the one hand, to free up capital to invest in clean or low-carbon energy. On the other, to fund and develop new “advantaged” (lower cost, lower emission) oil and gas assets. As a result, the risk of stranded assets remains very real in the transition strategies of the oil majors. So much so that under current potential exploration plans, the world’s largest oil and gas companies may sanction USD 1 trillion of assets that will be rendered inoperable before the end of their lifetime due to regulatory and economic pressures. This is about 50% of all assets that the oil and gas industry might try to build, Carbon Tracker estimates.

Source: BNEF

Plans to expand gas businesses run counter to decarbonisation pledges. The role of gas in the portfolios of the oil majors has risen steadily for more than a decade. Between 2007 and 2019, the share of gas output for seven of the largest oil and gas majors – ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, TotalEnergies, BP, Equinor and Eni – rose from 39% to 44%. Now, the oil majors hope to accelerate the shift from oil to gas. Shell has said it will invest USD 4 billion each year to expand its natural gas production as it shrinks its oil business – more than it will commit to clean energies. Despite committing to a 40% decline in oil and gas production, BP still envisions its liquefied natural gas (LNG) capacity to double to 30 million metric tonnes (mtpa) a year by 2030. TotalEnergies too will more than double its LNG capacity to 40 mtpa by the end of the decade.

This transition to natural gas is likely to help those majors with intensity-based targets as gas is 15% less carbon intensive on a lifecycle basis than oil. This further illustrates the necessity for emissions reduction targets to be expressed in absolute terms. If it is sufficient for an oil major to simply increase its gas production at the expense of oil to meet a target, then that target is not aligned with reaching net-zero.

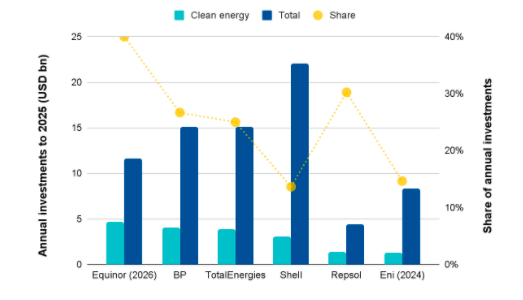

Oil majors are committing larger shares of their investment to clean energy, but the shift remains sluggish. Spending on low-carbon sectors has been highly concentrated over the past five years. TotalEnergies, Equinor, Shell, BP and Repsol have been responsible for more than 71% of all low-carbon investment in the sector, about USD 72.5 billion, according to BNEF. However, this is dwarfed by spending in other areas of the business – over this period, these same oil majors only allocated on average 5% of their annual investment budgets to clean energy ventures. And they were the biggest spenders.

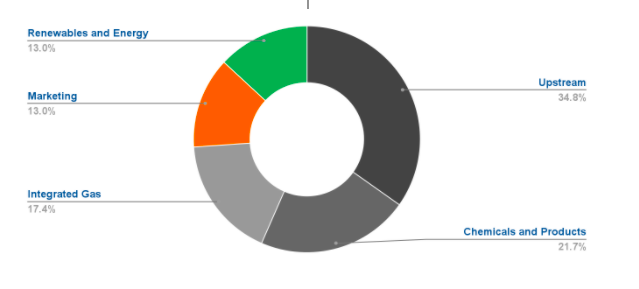

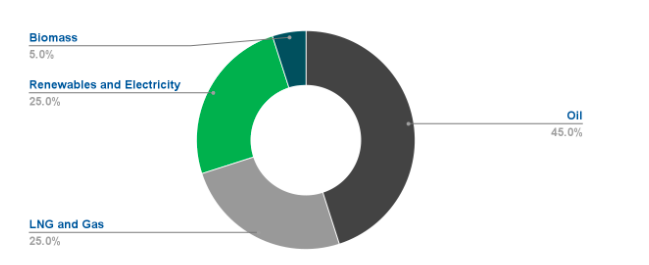

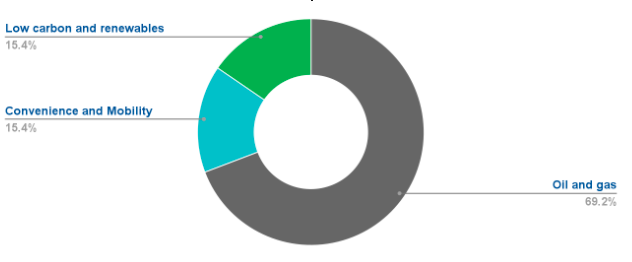

But the share of capital allocated to clean energy is rising. BP aims to invest USD 4 billion annually in clean energy by 2025. By the end of the decade, it will steadily increase this amount to USD 5 billion. TotalEnergies will dedicate USD 3 billion a year, while Equinor wants to spend USD 4.5 billion annually on clean energies over the next six years. Shell’s investment strategy lags behind the rest (see appendix II). With about USD 22 billion of planned annual investments over the next few years, only USD 3 billion (13%) will go to its ‘renewables and energy solutions’ business. This is less than the company plans to spend on marketing. Across the six European majors, the average share of capital allocated to ‘low carbon’ energy sources between now and 2026 is 24% (see Figure 3).

Source: Company reports

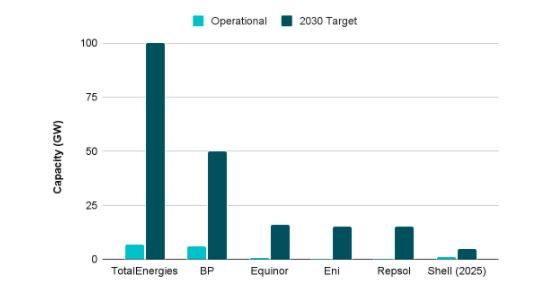

Moving into clean electricity helps clean operations and diversify revenue streams. Most majors have set out a renewable energy procurement goal. TotalEnergies and BP’s targets stand out for their scale – they target 100 GW and 50 GW respectively of renewable energy capacity by 2030. But their current operational capacity is still tiny – TotalEnergies has less than 10 GW of operational capacity, while BP has just shy of 6 GW. To meet these targets, therefore, these companies will have to build huge amounts of renewable energy (see Figure 4).

Source: Company reports

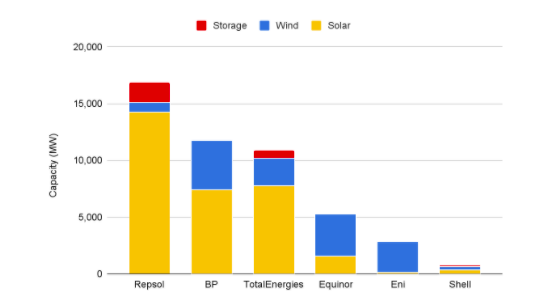

Most clean energy investments have gone into either wind or solar. Onshore and offshore wind projects have been the investment destinations of choice for the oil majors, attracting USD 25 billion over the past five years. Solar came in second, receiving USD 15 billion. Most of these projects have either been in North America or Europe. Looking forward, offshore wind appears to be one of the most attractive renewable energy sectors for the oil majors due to its synergies with constructing offshore oil and gas platforms. With their deep-pockets, oil majors have been able to bid up the price for rights to develop projects in auctions, which has put pressure on incumbents like Ørsted.

This year, however, most renewable energy deals have targeted solar. In the first eight months of 2021, the majors secured more than twice as much solar as wind – an estimated 32 GW compared to 14 GW (see Figure 5). Rather than representing a shift in preference to solar, this has been driven largely by huge, one-off deals. BP acquired a 9 GW solar pipeline in the US and Repsol bought a 40% stake in Hecate Energy, which has a 40 GW portfolio.

Source: ZCA tracking of company announcements; NB: Capacities are equity-adjusted

Shell is noticeably less focused on renewables than its peers, as it expands its presence in the power sector. Its decarbonisation strategy makes no mention of expanding its renewable energy procurement target of 5 GW by 2025, but stresses that the company will double its electricity sales to 560 TWh. It does, however, have the most ambitious targets for electric vehicle infrastructure, aiming to build 2.5 million charging stations globally by 2030, up from 60,000 today. Most oil majors already operate vast networks of diesel and petrol refuelling stations, and building charging stations is one way in which the majors can manage the transition away from petrol and diesel vehicles.

Alongside their strategic investments in new sectors, the oil majors are exploring avenues to reduce the climate impact of their fossil fuel assets. They are chiefly looking at offsets and the group of technologies that constitute carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Oil majors see offsets as the main vehicle through which to achieve their net-zero targets. They buy credits issued by projects that theoretically reduce the amount of CO2 entering the atmosphere, or avoid emitting it, thereby ‘offsetting’ their own emissions. The majors rely on voluntary offset markets to trade these credits. Most of these markets are overseen by non-governmental organisations and registries, such as the Voluntary Carbon Standard. However, in practice there are a number of problems with offsetting.

The oil majors are overly reliant on nature-based solutions (NbS). For instance, all of the 5.2 million carbon offsets that Shell has used so far have come from either protecting or planting forests. The company aims to offset 120 MtCO2 by 2030 with NbS – one prominent example is the Cordillera Azul project in Peru, where the Anglo-Dutch major claims that by preventing 1.6 million hectares of forest from being cut down, it will avoid 16.2 MtCO2 of emissions. And it is not alone. The Italian major Eni wants to use NbS to help it offset 6 MtCO2 a year by 2024, while TotalEnergies will aim to offset 5 MtCO2 annually between now and 2030. All well and good, but these three companies alone would need 20 million hectares of land to meet these requirements, according to an Oxfam report. This is roughly equivalent to the size of Cambodia.

But the amount of land required is not the only problem. There is a growing body of research that clearly indicates only a rich and biodiverse ecosystem adequately captures and sequesters carbon. Many NbS projects that focus on planting new forests create commercial monoculture (single species) plantations, or use non-native species that are less effective at removing carbon from the atmosphere and storing it than mature forests. Some of these projects have also fuelled deforestation, and failed to deliver climate benefits and support people’s livelihoods. Several companies inflate the amount of carbon that a forest offsets, with a recent paper finding that 90% of carbon offsetting projects using NbS failed to meet sustainability criteria. Indeed capturing carbon within newly-planted trees is not a permanent solution, as wildfires, land-use change and environmental degradation can all lead to the carbon being re-released. Ultimately, companies need to recognise that relying on NbS will never be a substitute for decreasing their own emissions.

Crucially, most traded offsets do not even remove carbon from the atmosphere. Renewable energy generation and preventing deforestation accounted for 34% and 32% respectively of all offsets used by December 2020. These projects merely avoid more carbon from entering the atmosphere or preserve the status quo. In other words, they do not really offset at all, as they do not reduce emissions in the absolute toward net zero. In fact, only 4% of offsets in the market, through planting trees, actually remove carbon from the atmosphere.

The use of offsets has led to absurd marketing claims. TotalEnergies and Shell have boasted of selling “carbon-neutral” liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargoes, whose emissions have, supposedly, been offset or avoided. In fact, most emissions created by these LNG shipments were not avoided or cancelled out. Nevertheless, the market for carbon-neutral LNG surged past one million tonnes in 2021, with buyers in East Asia driving demand. The growth of this market portends an increase in the use of offsets to justify selling more fossil fuels, which will ultimately lead to more emissions.

There is powerful, renewed interest in CCS. Although this group of technologies has existed since the 1970s, global CCS capacity remains small. At the end of 2020, the world had a mere 40 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of capture capacity, spread across 28 projects. This is less than 4% of Shell’s total emissions. Yet today’s rising carbon credit prices, particularly in the EU – which have hit a record EUR 60 a tonne – have led some to speculate that CCS might become increasingly feasible. The amount of investment poured into these projects reflects this expectation.

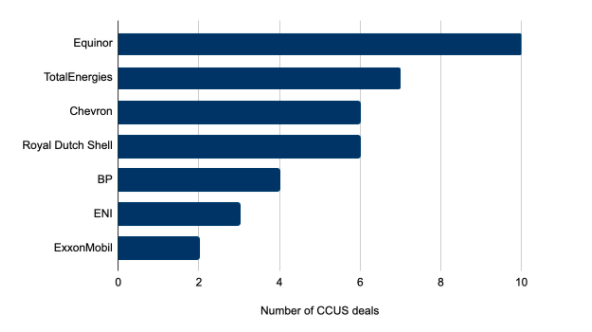

In 2020, USD 3 billion went into various CCS projects, up from USD 1 billion in 2019. If current projections are to be believed, over 190 mtpa of capacity will come onstream by 2030 – a 400% increase from 2020. Thus far, there have been 33 new projects announced in 2021 alone. The oil and gas industry is increasingly driving the momentum behind CCS. In 2020, the industry invested USD 690 million in CCS, the most since 2016, accounting for about 23% of total investment. In 2021, oil and gas companies have been involved in 18 out of the 33 deals closed so far in 2021, according to BNEF. These deals range from large industrial projects like Northern Lights and Porthos to building gas-fired power plants fitted with CCS. Equinor and TotalEnergies have been the most active in this space (see Figure 6).

Source: BNEF

But there are concerns about the scalability of CCS. Despite rising carbon prices and stronger commitments from governments and industry, the CCS sector has long been plagued by false starts. Only 28 of the 260 projects that were in development between 1995 and 2015 were actually built. The main reason for this was prohibitively high costs – adding CCS to a power plant or a refinery costs billions of dollars. Installing a capture facility on a natural gas processing plant – where gas is readied for distribution – theoretically makes economic sense at a carbon price of USD 27 per tonne, according to the Global CCS Institute.

However, this does not factor in the added cost of distributing and storing the captured carbon – such as building a pipeline to transport it. In reality, the carbon price necessary is likely to be far higher. As a result, maintaining high levels of fossil fuel production and simply adding CCS capacity would not make commercial sense for any oil major.

Capture rates of CCS projects are also far from sufficient. While CCS should theoretically capture up to 90% of emissions, in reality capture rates often only start at 65%, before gradually increasing to 90% after several years. This leaves plenty of time for projects with added CCS capacity to emit plenty of CO2. Even if it did reach 90%, a substantial amount of CO2 would still be emitted into the atmosphere. Therefore, the technology cannot be considered carbon neutral.

Broadly, scopes 1 and 2 are referred to as an oil major’s operational emissions. On average, these account for 15% of its emissions profile. The remaining 85% comes from scope 3 emissions.

Oil majors operate large, complex businesses and it is not always obvious how much of its portfolio is covered by a net-zero target. There are basically two types of assets:

Net-zero targets set their sights on 2050, which is still three decades away. For such a target to be credible, it needs to have interim targets that signpost progress and for which the company can be held accountable. Interim targets can set goals for 2025, 2030, 2035, etc. They provide the roadmap for emissions reduction.

A good net-zero target does not backload – i.e. push back – decarbonisation efforts beyond 2030. It aims to reduce emissions as quickly as possible and, therefore, sets out a pathway to make serious cuts to its emissions footprint this decade.

Source: Shell

Source: TotalEnergies

Source: Bloomberg Intelligence

Increased momentum in the energy transition has led the IEA to reduce its gas demand forecast for 2040 by 1,500…

Azerbaijan's climate and renewable energy efforts are dwarfed by its gas export expansion plans.