Report: Indonesia’s just energy transition partnership

The Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership (I-JETP) is a landmark climate finance agreement reached between Indonesia and a group of…

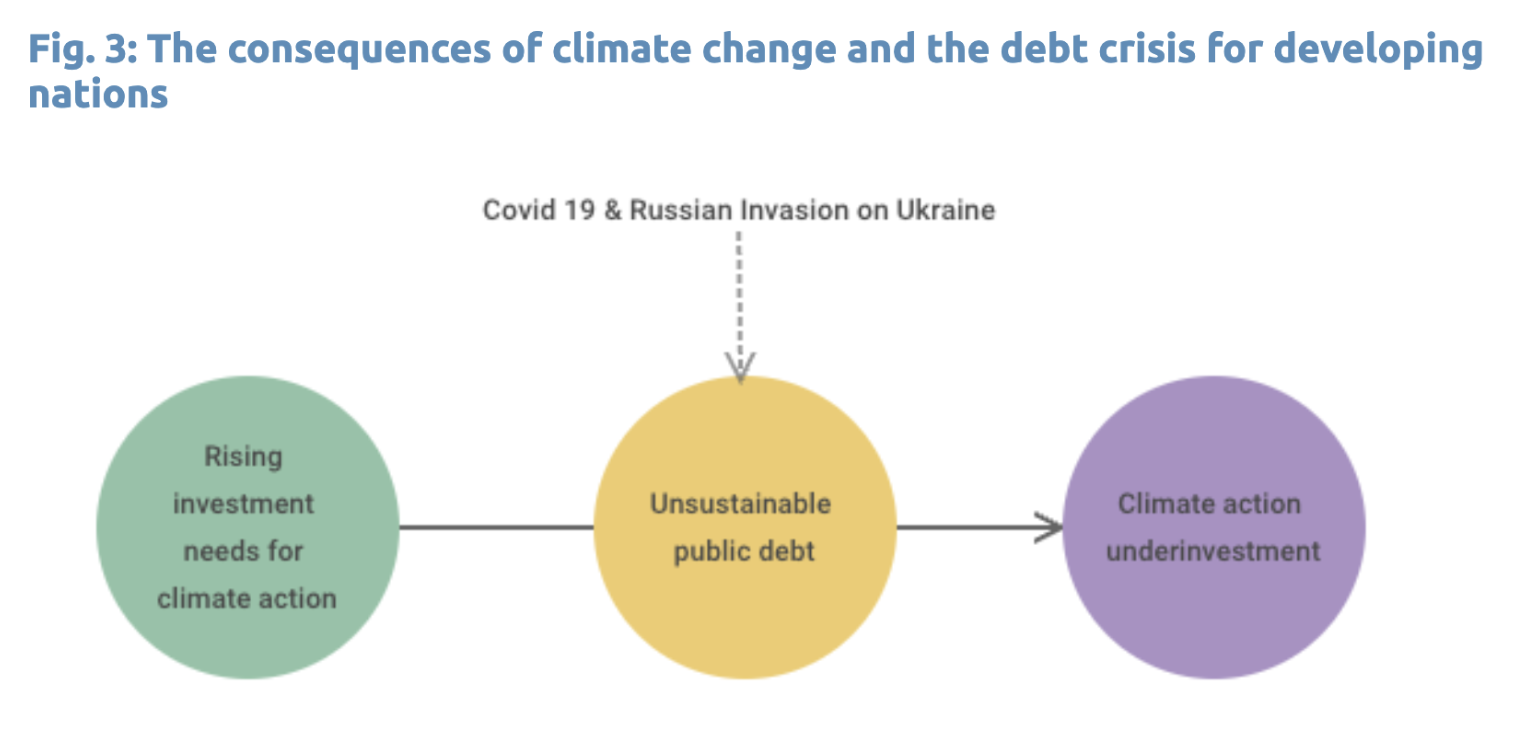

The world is suffering from the economic fallout of the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The recovery has been particularly difficult for developing nations. At the same time, climate change is fuelling the accumulation of debt in countries in the global south.

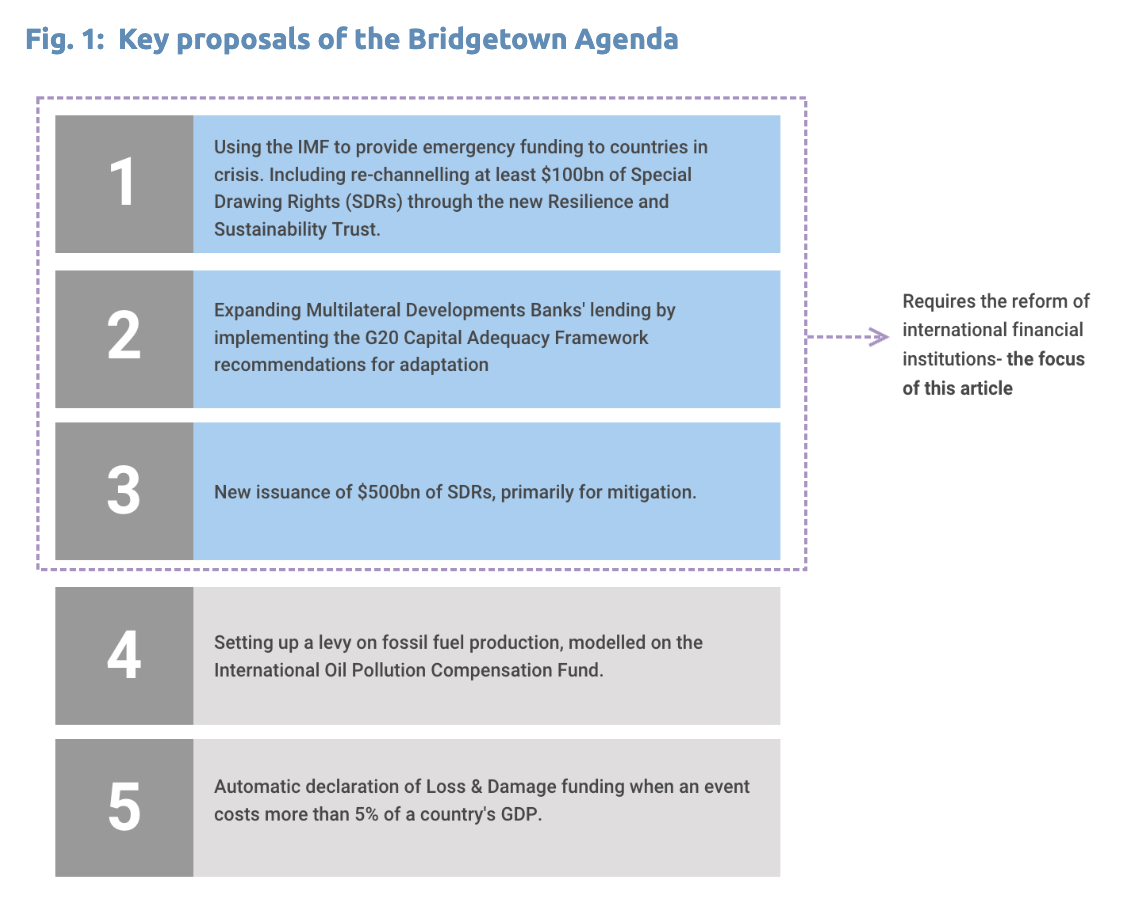

Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados, is leading the Bridgetown Agenda – a proposal outlining the reforms needed if global financial institutions, such as the IMF and WB, are to provide proper support to climate-vulnerable countries.

The proposed reforms of international financial institutions are a response to three interconnected crises – the Covid pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and climate change.

The Covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine severely impacted global supply chains, resulting in widespread economic shutdowns. The economies of developing nations are yet to recover.

Additionally, since Russia invaded Ukraine, a major producer of wheat and grains, food prices have increased sharply, creating a serious issue for import-dependent poorer countries, such as Sri Lanka, Lebanon and Senegal. Although Sri Lanka was already heavily indebted before the conflict in Ukraine, the rise in food prices pushed the country to default on its foreign debt.[1]Sovereign default is the failure by a country’s government to pay its debt when due. Several other developing nations are experiencing food shortages, while some are dangerously close to a debt crisis.

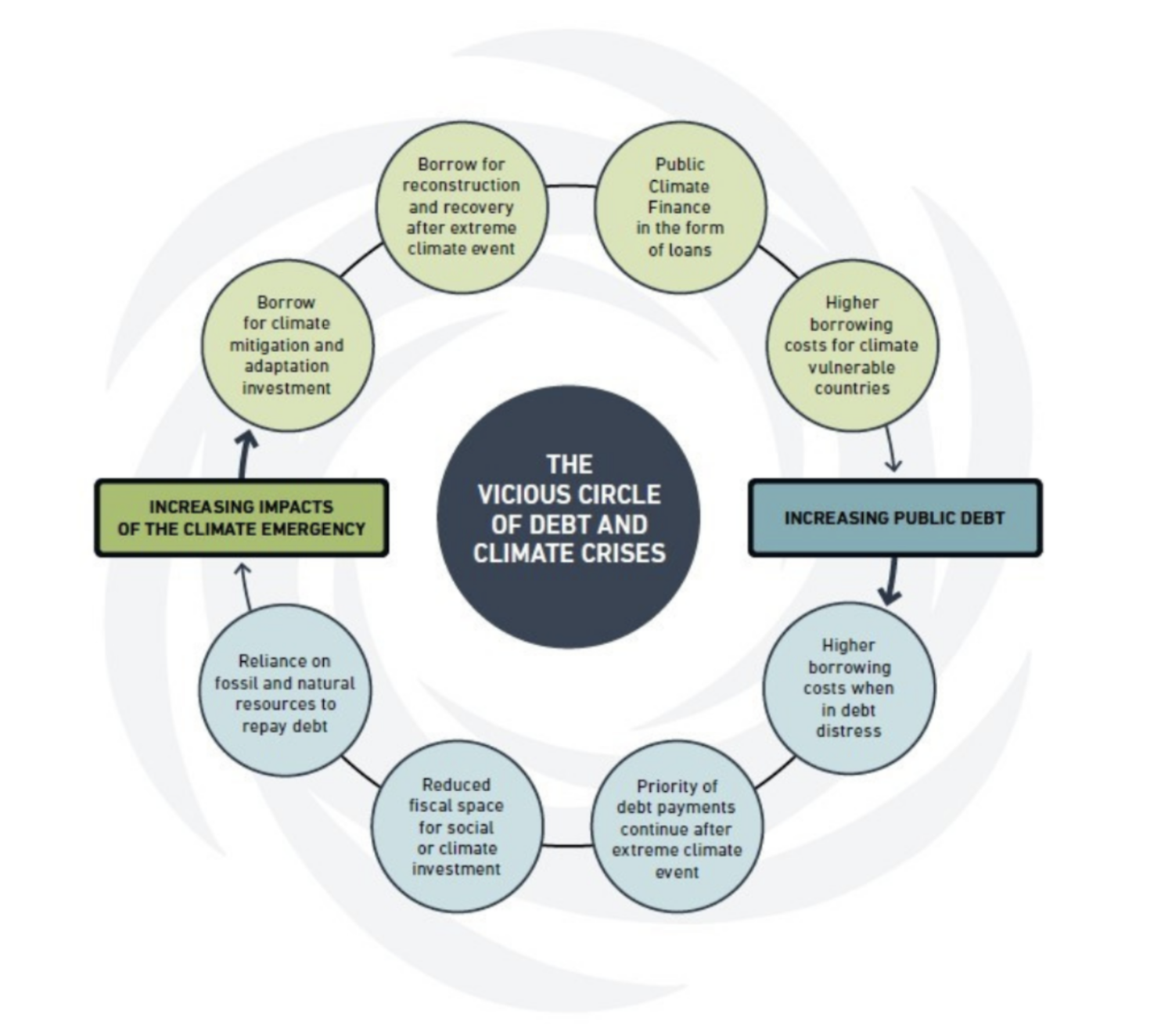

Meanwhile climate change is fuelling debt accumulation for vulnerable nations, which have little or no option other than borrowing to deal with recovery and reconstruction costs. When an over-indebted country is affected by such an event, existing debt makes it more difficult for that country to respond, as money is spent on servicing the debt rather than climate adaptation or responding to loss and damage.

Stable currencies, such as the US dollar, dominate global trade – 80% of trade is invoiced in emerging markets in US dollars. Since most countries cannot accumulate significant debts in their own currencies, due to the risk of currency devaluation, they must acquire dollar reserves. These reserves are usually held in the form of dollar-denominated benchmark assets, such as US Treasury bonds, which a country’s central bank can use to finance trade and support its currency’s value. Agricultural commodities, such as wheat and grain, are also traded using US dollars.

Starting at the beginning of 2022, central banks began hiking interest rates in order to curb rising prices. The combination of high interest rates and strong dollar can be disastrous for developing nations, because emerging markets rely on foreign investment and foreign capital. A stronger US dollar and higher interest rates can make servicing the dollar debt more difficult, as the dollar appreciation makes it more expensive for countries to buy the US currency they need to pay off their debts.

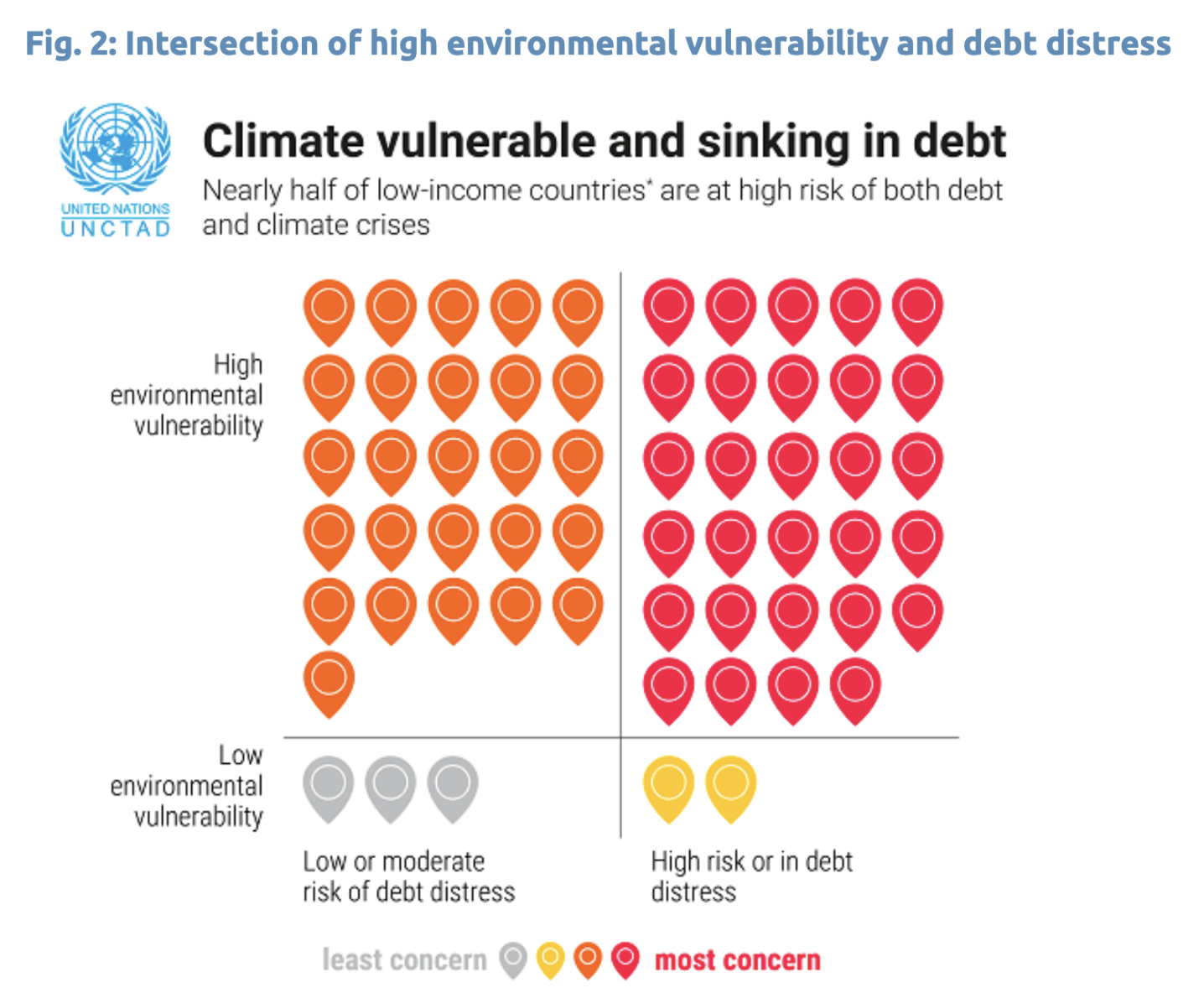

Since the beginning of 2022, developing countries’ foreign currency reserves have collectively fallen by USD 379 billion (from approximately USD 7.82 billion to USD 7.45 billion), the most significant drop since 2008. With depreciating currencies, countries without large reserves struggle to buy dollars to import critical goods and to service their debt. In 2021, developing countries paid USD 400bn in debt service, more than twice the amount they received in official development aid. About 60% of the poorest countries are either already in debt distress or are at high risk of debt distress, making it very difficult for them to make any future investments, according to the World Bank. Such investments include climate-resilient infrastructure, for example concrete seawalls or storm shutters to protect from hurricanes. As a result, heavily-indebted countries do not have the capacity to deal with climate disasters.

The Bridgetown Agenda advocates providing emergency liquidity to alleviate debt together with rechanneling funds that would allow vulnerable countries to make necessary investments to shift to a low-carbon world. Addressing climate change without addressing the debt crisis will not be possible.

Climate change is causing a surge in debt accumulation among developing economies. UNCTAD reports that nearly half of the low-income countries currently in or at high risk of debt distress are also highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change (UNCTAD, 2022). At present, countries in the global south are spending five times more on debt repayments than they are on addressing the impact of climate change.

Achieving climate-resilient structural transformation will require developing countries to take on even more debt. Currently, over 70% of public climate finance takes the form of borrowing and is primarily channelled into climate mitigation. Meanwhile, the UN Environment Programme estimates that annual adaptation needs for developing countries could amount to USD 340 billion by 2030 and USD 565 billion by 2050.

To effectively address the challenges posed by climate change, Covid and the war in Ukraine to developing nations, the way in which the global financial system provides funding must be reviewed. Currently, developing countries have limited access to private capital markets and are increasingly relying on international financial institutions for support. To ensure that these countries can build climate resilience and sustainably meet their long-term development needs, their access to financing on terms favourable to both debt sustainability and development needs to be improved. To help bridge the development gap and secure development finance, multilateral initiatives and Multilateral Development Banks need to step in and offer support.

According to the implementation plan agreed at the COP27 UN climate change summit in Sharm El Sheikh, the global transition to a low-carbon economy will require an investment of at least USD 4 trillion a year. To achieve this goal, reform of the WB and IMF is necessary. As Mia Mottley stressed last year when addressing the UN assembly, these lenders “no longer serve the purpose in the 21st century that they served in the 20th century”.

The WB and IMF, also known as the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs), were created to rebuild the international economic system after World War II. During the post-war period, they were influenced significantly by the US’s geopolitical strength, which is still reflected in their governance.

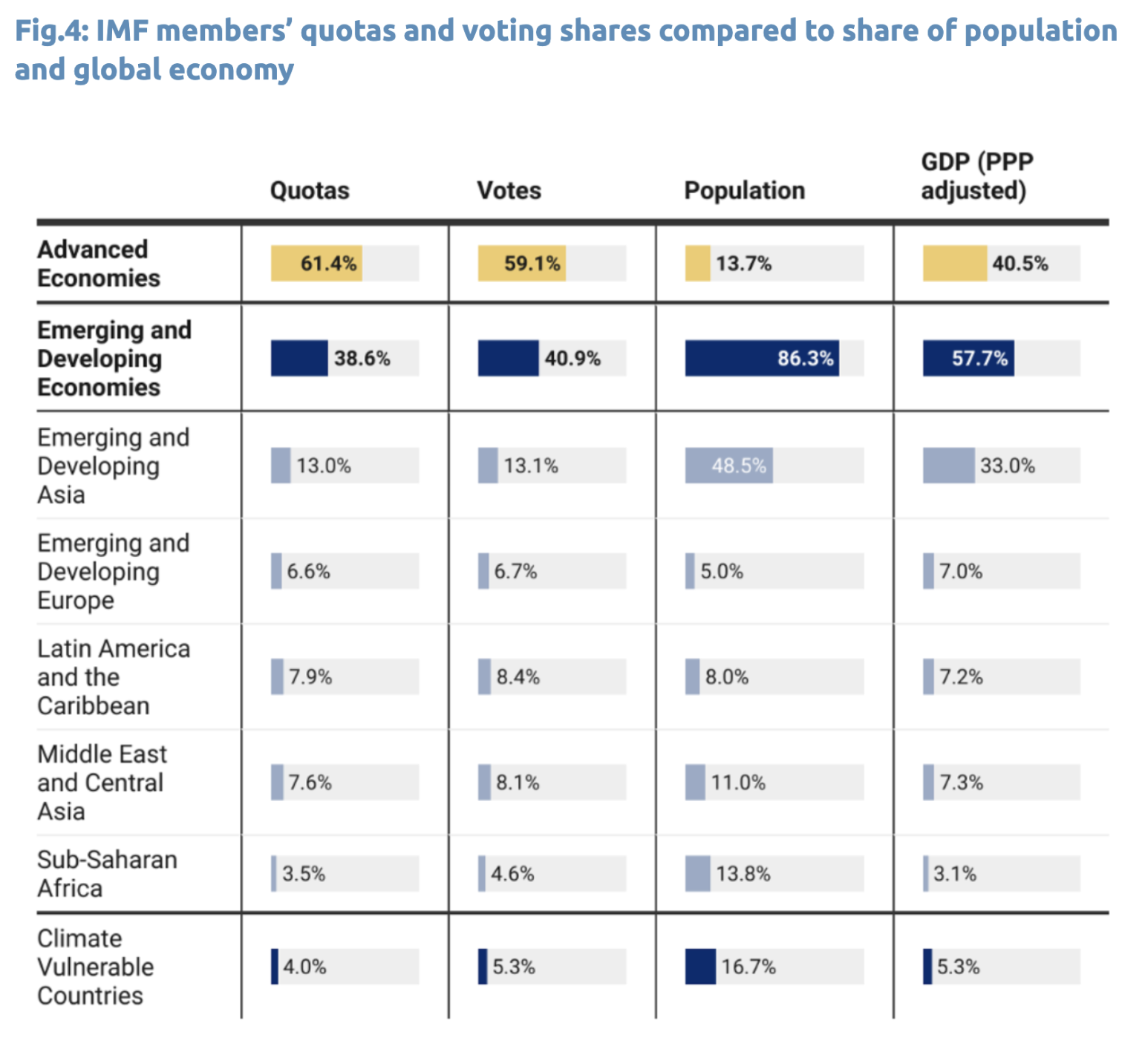

But the role of the WB and IMF has evolved over the years – the IMF now oversees the stability of the world’s monetary system, while the WB’s goal is to reduce poverty by offering assistance for development to middle and low-income countries. However, the distribution of voting power remains severely imbalanced in favour of the US and EU:

The voting shares are based principally on economies’ size and “market openness”. However, emerging market countries do not have voting shares corresponding to their current economic importance. Emerging and Developing Economies (86% of the global population) are often the recipients of loans from the BWIs. However, they are under-represented in decision-making processes. The same applies to countries that are vulnerable to climate change.

The Bridgetown Agenda advocates for practical measures that can address the inequalities at the core of international financial institutions and highlights the role that the IMF and Multilateral Development Banks have in response to the Covid pandemic and Ukraine war, as well as to assist countries in meeting their long-term goals, including combating climate change. The Agenda highlights Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), reserve assets of equivalent quality to dollar assets that can be issued by the IMF (see box below).In 2021, equivalent to about USD 650 billion of SDRs were distributed to help countries struggling with the impact of Covid. However, the SDRs were distributed according to the IMF quota, as they have been historically.[3]A quota formula is used to help assess members’ relative position in the world economy. The current formula was agreed to in 2008 and can be found on the IMFs website. On this basis, the … Continue reading Therefore, most go to developed economies and China, countries that do not need these extra reserves. (For more background on SDRs, see this primer by the Center for Global Development). The Bridgetown Agenda demonstrates that SDRs can be rechanneled to vulnerable countries to tackle structural challenges, including climate change.

SDRs were created by the IMF as an international asset to supplement the reserves of member countries. They are not a currency and cannot be used directly to purchase anything. However, being a medium of exchange, they provide a country with liquidity.

When a country needs hard currency, it can use its SDRs and exchange them for another member’s reserves such as dollars, pounds or euros. For example, if a country lacks foreign resources to import goods, SDRs can be exchanged for hard currency. They can also be used as payments to other SDRs holders (for instance to service debt).

On 31 October 2021, the G20 pledged to recycle USD 45 billion of its allocated SDRs towards the most vulnerable countries as a step towards USD 100 billion voluntary contributions to help lower-income countries struggling to recover from Covid and the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Efforts to rechannel the SDRs by developed countries are being tracked by The One Campaign initiative. As of February 2023, a total of USD 60 billion worth of SDRs have been pledged (excluding USD 21 billion from the US, which Congress has not yet authorised). However, although developed nations have committed to recycling SDRs to countries in need, the process of actually transferring the SDRs to those countries is not straightforward.

So far, the IMF has confirmed two channels to recycle SDRs: the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGT) and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST). The Fund aims to absorb about USD 65 billion worth of SDRs across these two channels. In the case of PGRT, more details are yet to come. The IMF is making progress on RST rechanneling, but it has yet to distribute any money from it. It has so far committed to lend USD 2.5 billion of SDRs to five countries: Costa Rica, Barbados, Rwanda, Bangladesh and Jamaica. The IMF Board approved the first four loans, with Jamaica’s approval pending.

The RST is a loan-based trust that could help low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries build resilience to shocks and achieve sustainable and inclusive growth. The main objective is to provide affordable long-term financing to support countries as they tackle structural challenges, including climate change.

In principle, the RST’s resources would be mobilised voluntarily from members who wish to channel their SDRs or currencies for the benefit of poorer or vulnerable countries.

All low-income countries, all developing and vulnerable small states, and all middle-income countries with per capita GNI below around USD 12,000.[4]This correlates to the eligibility of a country for International Development Association support, which depends on a country’s relative poverty, defined as Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. … Continue reading

Not every eligible nation will qualify for RST support. An eligible member would need a package of policy measures consistent with the RST’s purpose. Countries also need to show they can repay the loan, demonstrate how they would use the support with policies such as carbon-cutting, and already have a programme of policy reforms with the IMF.

Other recycling options must be explored to live up to the USD 100 billion commitment of the G20. So far, the IMF has approved five new institutions as prescribed holders of SDRs. These include the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, the Caribbean Development Bank and the Latin American Development Bank (CAF).

The Bridgetown Agenda proposes a Global Climate Mitigation Trust backed by USD 500 billion in SDRs for climate and development. The trust-funded projects would have to pre-qualify using proven technologies and have high environmental, social and governance standards. Investment managers would choose them based on how much and how fast they could reduce global warming.

The IMF plays an important part in the reforms needed to tackle climate change. However, other key stakeholders exist in this regard, namely MBDs. These banks have a mandate to prioritise development over commercial interests. An increasingly popular view is that MDBs have not effectively delivered the necessary aid to address pressing challenges like climate change, particularly for the developing nations that are most in need.

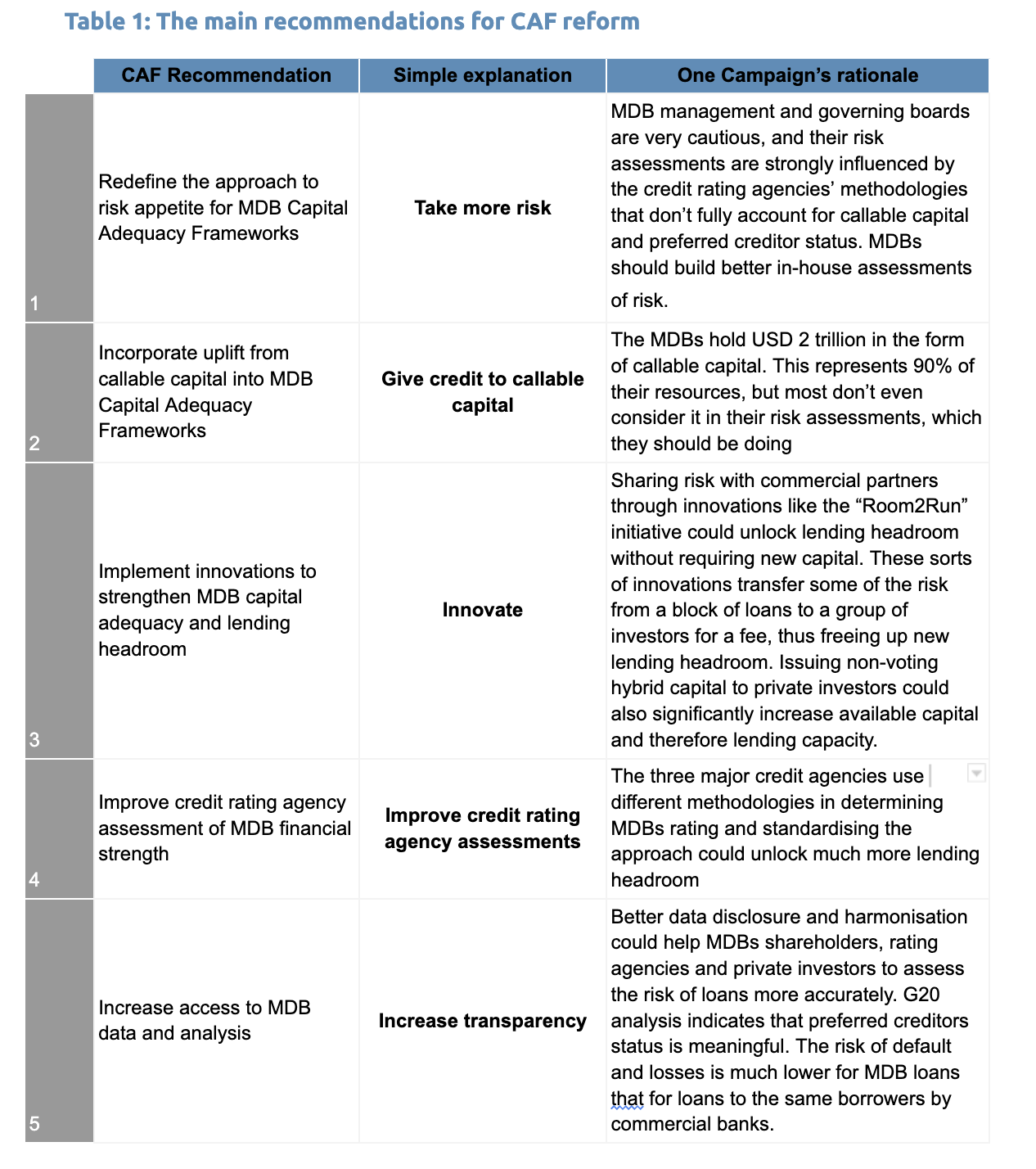

The Bridgetown Agenda stresses that the WB and other MDBs must increase lending to USD 1 trillion and prioritise building climate resilience in vulnerable countries. This can be achieved by implementing the measures recommended by the G20 Capital Adequacy Frameworks (CAF) Review (see Table 1 below). Multilateral development banks are owned by countries that signed up to an international treaty – they make up the shareholders. Some of them are borrowers, some are donors, some are both. MDBs collectively hold over USD 1.8 trillion in assets that could potentially be leveraged for lending. Typically, a government applies to the bank for a loan. Legal, policy and technical experts then advise on the loan structure and the policies needed to make it work.

Most MDBs have two lending facilities, called windows:

Concessional loans have more generous terms. Generally, they include below-market interest rates or grace periods in which the loan recipient is not required to make debt repayments. This type of finance targets high-impact projects responding to structural challenges – from climate change to vaccine deployment – that would not be realised without specialised financial support.

MDBs offer concessional funds to those countries with a GDP per capita of less than USD 1,253 a year (12% of the world’s population). However, during Covid, some middle-income countries that were particularly badly hit were granted temporary access to concessional borrowing. Similarly, broader eligibility for climate-vulnerable countries is much needed.[5]62% of the world’s poor live in middle-income countries where around 5 billion of the world’s population live. UNCTAD recommends using the UN Multi-Vulnerability Index (MVI) as a criterion for … Continue reading

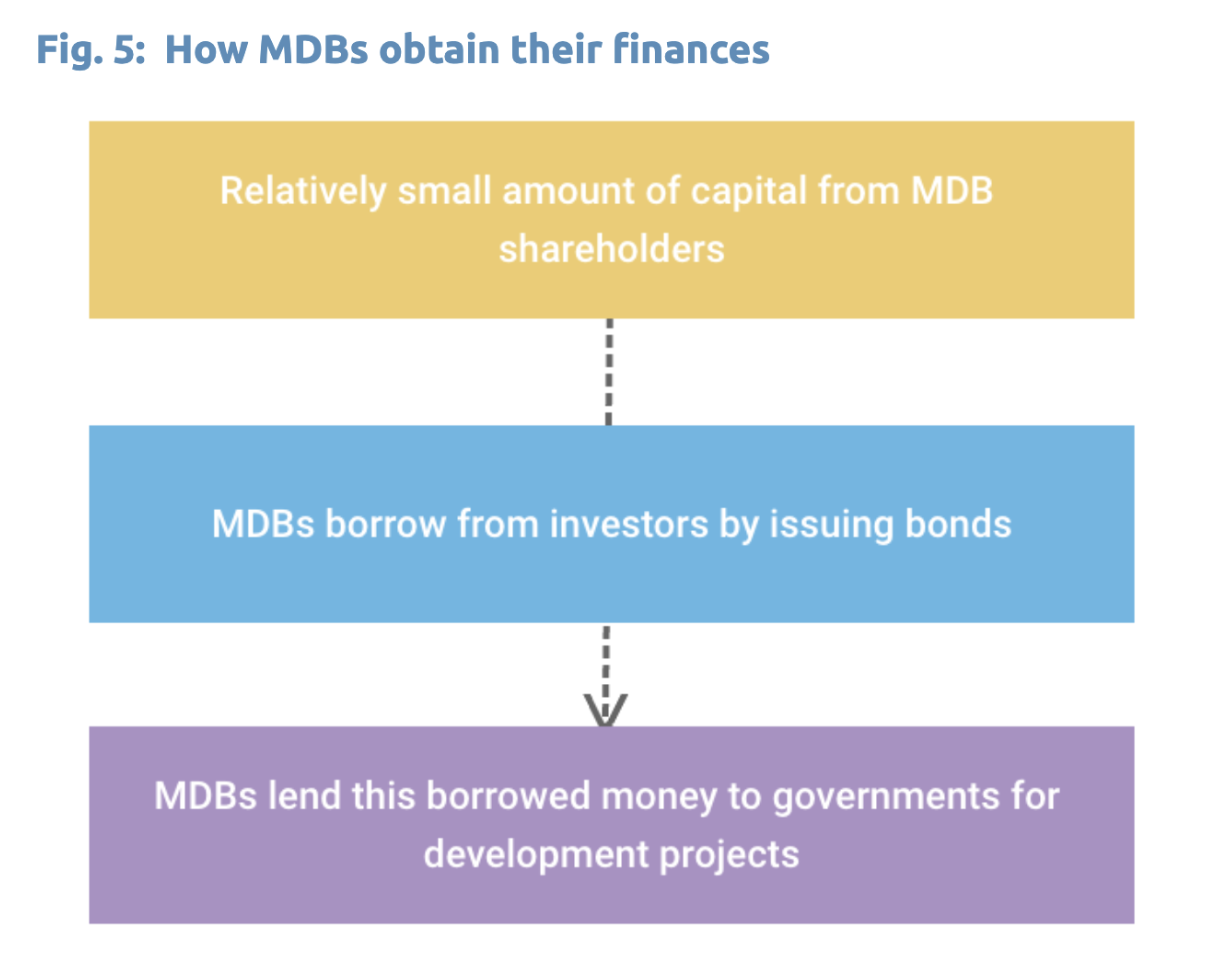

MBDs obtain most of their funding by borrowing on international bond markets. They turn small amounts of capital from shareholders into substantial resources for lending. By issuing bonds, they increase the amount that is available to lend countries for development at a cheaper rate and better terms than countries could access themselves. This is very effective – since 1944, the WB has taken USD 19 billion of cash from shareholders and turned it into over USD 800 billion of lending.

MDBs have a solid financial track record and, therefore, can borrow from bond investors at relatively low rates. They are considered a secure investment because:

MDBs are subject to regulatory capital and liquidity standards, as well as rating methodologies, that were adapted from those developed for commercial banks and do not reflect MDBs’ mandate to prioritise development over commercial gains. As a result, the WB manages itself according to a level of risk that can be even lower than that represented by a AAA rating. While great for its credit ratings, the Bank’s ‘robust risk management system’ seems at odds with its development mandate, as it remains focused on financial risks instead of developmental investments. The WB’s focus on its credit rating needs urgent rethinking. Importantly, more lending for vulnerable, developing countries could be generated if rating agencies refined their methodologies to reflect MDBs’ low risk status (more detail can found here).

The MDBs each have different adaptations and capital and liquidity buffers. The larger the buffers, the more constrained the MDBs will be in their financial capacity, reflected in their Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR).

Bond investors who provide MDBs with capital want to be sure that MDBs can repay their money. So currently, like all banks, MDBs must back up their loan portfolios with an adequate amount of their own shareholder capital to meet their financial obligations.

The CAR sets standards for banks by looking at their ability to pay liabilities and respond to credit and operational risks. A bank that has a good CAR has enough capital to absorb potential losses. Therefore, it has less risk of default and losing investors’ money.

The financial risks posed by MDB operations differ from those of commercial banks because of their official standing and development mandate. Despite this, their Capital Adequacy Frameworks do not reflect their unique strength, such as callable capital and preferred creditor treatment.

In addition, MDBs and the three main credit rating agencies (Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch) have different approaches to MDB capital adequacy. There is a strong need for MDBs to better coordinate engagement with rating agencies to ensure an appropriate understanding of their financial strength and shareholder support.

The G20 established an independent review to evaluate MDB capital adequacy (please see details below). The review panel concluded that government shareholders, MDB management and credit rating agencies had overestimated the financial risks of MDBs and underestimated their unique strengths.

In July 2022, a G20 expert panel released a report after being tasked with the independent review of MDBs’ Capital Adequacy Frameworks. The panel recommended five measures to modernise MDBs and to calculate their capacity to lend in support of climate and development objectives. Implementing the recommendations could unlock several hundred billion dollars in additional lending without posing a threat to MDBs’ financial stability or their AAA credit rating.

Source: ODI

References

| ↑1 | Sovereign default is the failure by a country’s government to pay its debt when due. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | At 17.43% of total voting power, the US has veto over major policy decisions. See https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF10676.pdf |

| ↑3 | A quota formula is used to help assess members’ relative position in the world economy. The current formula was agreed to in 2008 and can be found on the IMFs website. On this basis, the share of emerging market and developing countries is about 42.3 percent (about USD 275 billion), of which 3.3 percent (about USD 21 billion) is for low-income countries |

| ↑4 | This correlates to the eligibility of a country for International Development Association support, which depends on a country’s relative poverty, defined as Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. GNI does not differ significantly to GDP. GDP refers to the income generated by production activities on the economic territory of the country, whereas GNI measures the income generated by the residents of a country, whether earned in the domestic territory or abroad. |

| ↑5 | 62% of the world’s poor live in middle-income countries where around 5 billion of the world’s population live. UNCTAD recommends using the UN Multi-Vulnerability Index (MVI) as a criterion for concessional lending, where debtor countries borrow internationally on more favourable terms than in the open marketplace. |

The Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership (I-JETP) is a landmark climate finance agreement reached between Indonesia and a group of…

Key points: Asian governments and companies are trying to keep up with the global trend of developing voluntary carbon markets…