Report: Indonesia’s just energy transition partnership

The Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership (I-JETP) is a landmark climate finance agreement reached between Indonesia and a group of…

At COP26, a “historic international partnership” was agreed to support a just transition to a low carbon economy in South Africa. This Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) saw France, Germany, the UK, US, and EU (the International Partners Group, or IPG) commit to providing USD 8.5 billion over three to five years to support South Africa’s national climate plan. The finance could be provided as grants, concessional loans (with interest rates lower than would be available from commercial banks), through private finance, guarantees or technical support.

The JETP aims to phase out coal and rapidly accelerate the deployment of renewables in South Africa’s heavily coal-dependent electricity system. This would enable the country to reduce its emissions, consistent with keeping global warming below 2°C. A key focus of the agreement is supporting a just transition that protects vulnerable workers and communities – especially coal miners, women and youth – affected by the move away from coal. The partnership also aims to support private sector investment, including through changes to government policy in South Africa.

This agreement has been described as a potential “new model for climate progress,” a bespoke multilateral agreement developed by and for a single country with greater focus on ensuring a just transition. Even before the implementation plan for the South Africa JETP had been agreed, the model was replicated – in June 2022, the G7 announced it was “working towards” further JETPs with India, Indonesia, Senegal and Vietnam. Pilot projects to develop JETPs for Egypt, Ivory Coast, Kenya and Morocco were also announced at the EU-AU summit in February 2022. While the model has been quickly replicated for other countries, serious questions remain about the transparency, consultation and financing model of the South Africa deal.

An investment plan for South Africa’s JETP has been approved by the South African cabinet and is due to be publicly released during COP27. This implementation plan will play a pivotal role in shaping the financing of the energy transition in South Africa. It could also be seen as a crucial test of this new partnership model and a key milestone in demonstrating progress on delivering on funding commitments ahead of COP27.

JETPs could fill a key gap in international climate finance, between broad global-level funder commitments that lack detail and accountability and project-specific financing that does not provide a comprehensive approach to the energy transition. Instead, JETPs are country-led and bespoke – South Africa’s lead climate negotiator described the USD 8.5 billion package as “groundbreaking” because it was “co-created” by South Africa and donor countries, rather than imposed by wealthy nations.

Linked to this, JETPs are designed to incorporate national policy reforms alongside project financing. These policy reforms should be aimed at removing barriers to the investment and scaling up of clean energy technologies, for example through energy market or domestic subsidy reforms.

The energy transition has significant social impacts – most acutely on workers and communities that rely on high-emitting industries that need to be phased out. The transition also offers huge opportunities, with investments in renewable energy and infrastructure creating new jobs and economic growth. Significant government and international financing, alongside the right policies, are needed to mitigate the negative impacts of phasing out high emitting industries and ensuring those communities benefit from the shift to clean energy.

Ensuring a rapid phaseout of coal-fired power generation is essential to limiting warming to 1.5°C, with richer nations needing to end coal use by 2030 and a global end to coal power by 2040. Coal plants have an average lifetime of 46 years but to align with a 1.5°C goal, plants need to reduce their operational lifetime to an average of 15 years. The early closure of these power plants can come with significant financial costs as the high upfront costs are usually paid off over the life of the project. This is particularly acute in the global south where coal fleets are comparatively young and shorter lifespans would further reduce earnings and increase losses.

Proposals for how to finance the early retirement of coal power plants have developed significantly in recent years, including the possibility of running plants for a shorter period with a lower cost of capital, or buying out existing power-purchasing agreements. JETPs could provide a fully-developed model for financing an accelerated coal phaseout that could be replicated across coal-power dependent countries in the global south.

In parallel with the JETPs, the Asian Development Bank is developing an Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) for the early retirement of coal power plants. The ETM is currently developing pilots for combining public and private finance to retire or repurpose between five and seven coal-fired power plants in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Climate finance has become a key sticking point in international climate negotiations, with the failure of rich countries to deliver on the USD 100 billion commitment made in Paris a major block to progress at COP26. While pledges of funding have increased, governments in the global south are also keen to see those pledges delivered and flowing to projects and programmes that urgently need funding. Effective delivery of JETPs could show that donor countries are serious about meeting their funding commitments, building trust in the multilateral process.

G7 countries are not the only potential donors for energy infrastructure projects in the global south, with Russia and China also providing project financing. If the G7 countries want to maintain their position and influence as a provider of finance to global south countries, they must deliver on finance, and do it in a way that genuinely meets the needs of the recipient countries.

Of the proposed JETPs, South Africa’s is the most advanced, yet very limited information about the deal has been released publicly. While the South African government has conducted a countrywide consultation on the just transition, the consultations on the JETP itself have, so far, only involved the South African government, the IPG and development finance institutions. Apart from two events at COP26 in Glasgow, there has been no formal civil society consultation on the proposed partnership.

After the initial announcement at COP26, there was no public communication regarding the partnership for six months, until an update was released by the South African government and the IPG.

The South African government has been working on a proposed investment plan – the core of what the JETP will fund. A draft of the plan was reportedly sent to the IPG in early October, and was approved by the South African cabinet in mid-October. Unusually, public consultation on the investment plan is only due to take place after it has been agreed by both the IPG and the South African government, limiting the scope for meaningful input.

From the donors’ side, the IPG has sent financial offers to the South African government for evaluation – however these offers remain confidential. Again, the lack of transparency on the sources and types of funding proposed by the donors severely limits public scrutiny over the financing of the deal.

This lack of transparency and consultation is a key concern, as consultation and engagement with civil society, communities and trade unions should be a cornerstone of a just transition.

A core element of the JETP model is the use of blended finance, where public finance from governments is used to leverage further new private sector investment. This model has been proposed for over a decade and pitched as a way not only of ensuring greater value for money for donor governments and their taxpayers, but creating a greater role for the private sector in the traditionally government-focused world of development finance. However, real leverage rates – the ratio of public finance to private finance – are low. On average, for every USD 1 development banks have invested in low income countries, private finance has mobilised just 37 cents.

Part of the challenge with blended finance has been that public funding has come in the form of loans through development banks that have a mandate to deliver a return on their investment. This means that public finance can end up funding commercially-viable projects, rather than being used to take on greater risk or fund activities that don’t generate a return. In other words, the funding does not end up where it is needed most.

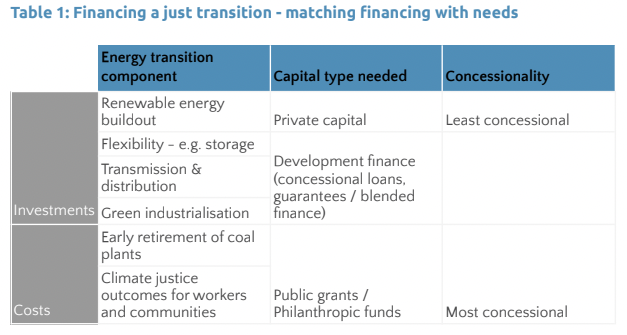

This will be a particular challenge for JETPs, as the financing covers a broad spectrum of needs with varying rates of return. These range from renewable energy generation to the costs of supporting communities and workers that need financial support. In order to be successful, public finance should be targeted at zero and low-return needs, which means the majority of the public finance should be provided as grants, guarantees or on highly concessional terms.

Adapted from Making Climate Capital work: Unlocking $8.5bn for South Africa’s Just Energy Transition by the Blended Finance Taskforce and the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University

Recipient countries have publicly stated that they are not interested in taking on more debt at near-market rates. As South Africa’s environment minister has said: “We would have no interest in borrowing money that isn’t cheaper, what would be the point?”

While the details of the financing for South Africa’s JETP remain confidential, early signs are not promising – in the case of funding currently being negotiated by France, reports suggest only a small portion would be in the form of grants, which would only cover research studies. Similarly, in early October the German government announced it had pledged EUR 320 million for the JETP, with EUR 270 million in low interest loans and only EUR 50 million in grants.

A leaked draft of the financing plan for South Africa indicated that just 2.7% of the total USD 8.5 billion would be provided as grants, with 43% provided as commercial loans or guarantees. These figures were disputed by South Africa’s lead official on climate finance, who stated that: “The numbers cited do not reflect the current status of the financing package, details of which will be provided once the plan is released to the public.”

Multiple studies have shown that to limit warming to 1.5°C, no further fossil fuel infrastructure can be built. Yet all five JETP countries have plans to significantly increase the use of fossil gas in power generation and Senegal is set to become a major new gas producer. The five countries alone make up 19% of gas power plant capacity currently under development in the world.

In many of the countries, these gas expansion plans are closely linked to the JETPs:

During COP26, 39 countries committed to end new direct international public finance for the unabated fossil fuel energy sector by the end of 2022 – with Japan the final G7 to join the commitment in May this year. However, this commitment contained an exemption to allow fossil fuel funding in limited and clearly-defined circumstances that are “consistent with a 1.5°C warming limit”. The commitment was further weakened at the G7 summit in June in the wake of the global energy crisis driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The group’s communique acknowledged that: “Investment in this sector is necessary in response to the current crisis… In these exceptional circumstances, publicly supported investment in the gas sector can be appropriate as a temporary response.”

In this context, the JETPs serve as a crucial test of whether the G7 countries will keep to their COP26 commitment to end international fossil fuel financing.

There are significant risks that JETP deals could finance ‘false solutions’ to the energy transition, either wasting scarce resources on unviable technologies or, worse still, financing technologies that actively harm the environment:

The Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership (I-JETP) is a landmark climate finance agreement reached between Indonesia and a group of…

Key points: The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) play a crucial role in providing climate…