Article 6 of the Paris Agreement at COP28: What is at stake?

Developing stringent rules for the global carbon market under A6.4 could set a precedent for high standards and restore faith…

The global system of industrial food production today is largely unsustainable. It is a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – accounting for up to 37% of total GHG emissions globally. Its processes erode soil nutrients and kill species, impacting biodiversity. Its structures allow power to be concentrated in the hands of a few corporations, contributing to the exploitation of workers and the impoverishment of small-scale farmers. The system also fails to feed the world, despite its claims and intentions – world hunger is on the rise, affecting 8.9% of the global population.

Many agricultural experts, scientists and activists agree that a radical transformation of our global food system is needed. In recent years, agroecology has emerged as a science-based set of practices and a social movement for a sustainable alternative to the global industrial food system. At its core, agroecology “centres on food production that makes the best use of nature’s goods and services while not damaging these resources”. It also involves the application of socioeconomic principles to build resilience and food system security.

Many experts, NGOs and multilateral agencies, including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), The High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE), and the Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Food, support agroecology. In addition, 12.5% of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) addressing climate change also include agroecology, with the governments of these countries considering it a valid approach to climate change.

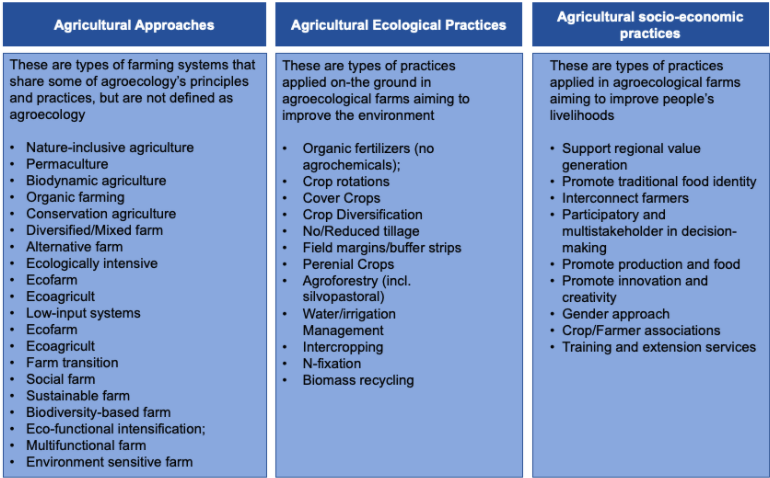

This briefing maps out the key concepts and current thinking on agroecology. It is important to note that there are competing terminologies being pushed in agricultural sustainability debates, especially in corporate commitments. Beware of exaggerated claims and vague terms that do not align with agroecological principles and thus do not help in transforming the food production system.

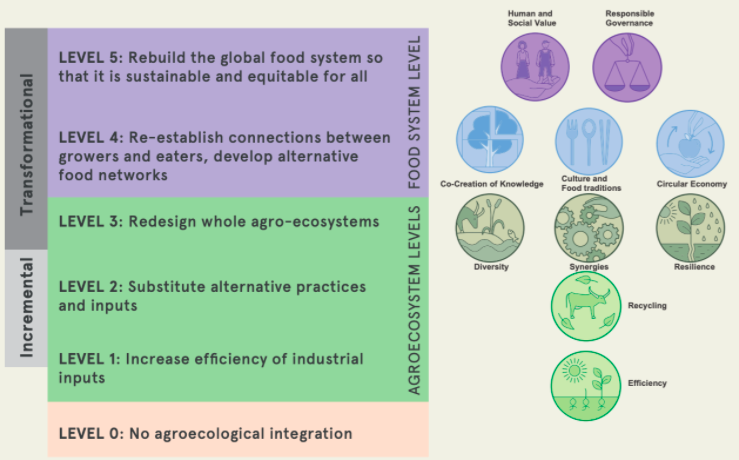

| What is agroecology? Agroecology is the application of ecological principles in agriculture. For example, replacing chemical inputs and optimising biodiversity, water and energy use. It is an umbrella term covering many agricultural practices, including organic, biodynamic and permaculture. Over the years, the definition of agroecology has expanded to include a food systems approach, encompassing economic and socio-cultural principles. For example, empowering farmers, supporting local food markets and promoting co-learning. It has been defined in many ways by many different stakeholders (1,2,3). As a broad set of approaches, it provides the flexibility to adapt to local contexts. The FAO developed a set of principles to help countries implement agroecology, which can also be used as metrics to evaluate corporate commitments. These ten principles span five levels of transitions towards sustainable food systems. These levels were adapted by the FAO from Gliessman, and can be used as a framework to evaluate the level of transformation of each agroecological practice. Higher levels yield more transformative changes. |

Source: FAO, 2020

Across the world, farms and communities are transitioning to agroecology, often delivering impressive results, especially when solutions are tailored to the local context. Worldwide, it is estimated that nearly 30% of farms have “redesigned their production systems around agroecological principles”. A growing body of evidence shows there a number of benefits from agroecology, including: [1]The literature is quite heterogeneous, with some studies focusing solely on agroecological farming systems and others on other systems that adopt agroecological principles, such as organic … Continue reading

Agroecology can increase yields and productivity, improving the availability and stability of food production (Box V, p.35-36). For example, yields can go up between 50%-100% (p.34) in certain settings, challenging the idea that ecological farming methods are less productive than conventional agriculture and, therefore, insufficient to feed the world. In 57 nations, agroecological projects covering 37 million hectares (equivalent to 3% of the total cultivated area in these countries) were shown to increase average crop yield by 79%, as well as land productivity on 12.6 million farms.[2]his is one of the widest and systematic studies on agroecology. It included 286 projects in six regions of the world: Sub-Saharan Africa; Middle East and North Africa; Europe and Central Asia; South … Continue reading[3]For example, average food production per household was up by 73% for 4.42 million small farmers growing cereals and roots. In Africa, farmers had even higher gains with average crop yields rising by 116%.[4]A reanalysis of the previous studies. It included 114 agroecological organic projects.

Some low-input agroecological systems, such as organic agriculture, can decrease yields. In developed countries, organic farms produced 8% lower yields than conventional farms.[5]Organic agriculture is included in literature reviews as a type of agroecological practice even though it is not as holistic as “agroecology”. However, higher yields and stability can be achieved when other practices that boost diversity are also in place, such as growing different crops in rotation or growing two or more crops simultaneously (i.e. intercropping).

Agroecology improves health as well as food security by increasing access to food and diversifying diets.[6]Hunger and malnutrition is not only a measure of food production, but of unequal access to food, inputs, markets, etc. Different agroecological systems can increase the level of beneficial nutrients in food, leading to more diverse and healthy diets. For example, organic milk and meat contain around 50% more beneficial omega-3 fatty acids than conventional equivalents. Agroecology can also help to avert the negative health impacts of conventional agriculture, such as diseases caused by pesticide use. In many countries – from Mexico and Nicaragua to Ghana and Kenya – agroecology methods have improved diets, health and the nutritional value of crops.

Agroecology improves soil health, biodiversity and ecosystem services, increasing climate adaptation and resilience. A recent literature review found that many practices improve soils and biodiversity (p.30-31), including soil organic carbon content, soil biodiversity and species richness.[7]FAO conducted the widest literature review to date about agroecology potential in increasing climate resilience. The meta-analysis from 2020 consisted of peer-reviewed studies on agroecology (n=34 … Continue reading[8]Examples are: the use of organic fertilisers, higher crop diversity, agroforestry, biodiversification, soil management, and water harvesting. These are central aspects of climate change adaptation, as they help farmers handle (p.467) climate extremes, particularly in the Global South. For example, in semi-arid and sub-humid areas in Africa and in 17 food-insecure countries, agroecological practices have been shown to help improve soil, crop and water management (p.15-20).[9]Debray et al. (2019) focused on agropastoral land use in semiarid Africa and mixed-crop-livestock production in subhumid areas.

Given that industrial agriculture is the source of agricultural emissions, transitioning the current system to agroecology could significantly contribute to mitigation. A recent literature review found that some practices, like using organic fertilisers and maximising resource efficiency, help to reduce emissions. For example, small agroecology farms may be two to four times more energy efficient than large conventional farms. Similarly, agroecological farming is more efficient in storing carbon in soils than conventional systems. Agroecological practices that rebuild the organic matter in soils lost from industrial agriculture, for example, can store an equivalent to 20%–35% of current GHG emissions, according to GRAIN. Agroforestry – growing trees in or near croplands and pasture – can store 0.1 to 5.7 Gt of CO2 a year globally (for reference, the higher estimate is nearly six times the aviation emissions in 2019), according to the IPCC.[10]In Africa, agroforestry’s potential is high even in very dry grassland areas, as only 15% of farms currently have 30% tree cover. Across the continent, the practice of growing trees and crops in … Continue reading But the mitigation potential can vary, depending on the type of practice adopted (p.33). For example, practices that focus only on improving soils can reduce emissions locally, but not necessarily globally.[11]Based on the current evidence, their potential has been overestimated. The World Resources Institute took a deep dive into the science and found it is “unlikely to achieve large-scale emissions … Continue reading More importantly, the mitigation potential of scaling up agroecology is achieved because it can reduce emissions of the industrialised food system as a whole. For example, by distributing food mainly through local markets instead of transnational food chains, total GHG emissions can be reduced by 10%–12%.

Agroecology increases incomes and creates more stable jobs. A recent literature review found that profitability and labour productivity increased in 66% and 100% respectively compared to conventional agricultural practices. Case studies in European farms show that farmers’ incomes can rise by 10% to 110%. In India, a project transitioning six million farmers to agroecology increased household food autonomy, income and health, as well as reducing farm expenses and credit needs. In Mexico, the combination of traditional indigenous knowledge with agroecological practices enabled 31,000 coffee farmers to obtain higher profit margins than conventional farmers.

A higher income reduces production costs and means farmers are less dependent on local retailers and moneylenders, and therefore less vulnerable to price volatility and debt. Agroecology also creates jobs at lower costs with work spread more evenly throughout the year, allowing for more full-time employment.

The current limitations to agroecology research and application:

Scale up is possible but requires the obstacles to transitioning away from industrial agriculture to be removed. Today, “the world spends at least USD 600 billion each year on agricultural subsidies. Roughly 70% of these funds provide direct income support, while only 5% support any kind of conservation or sustainability objective,” according to the World Resources Institute.

Governments, donors and the agro-food industry are the primary hindrance to agroecology. Policymakers are concerned about profitability and scalability and believe, mistakenly, that agroecology is too complex. This reduces their capacity to enact laws that foster agroecology. Through trade and agricultural policies, governments tend to favour the interests of the existing agro-food industry, such as providing agricultural subsidies to support conventional farming.[13]Subsidies have helped increase conventional farming productivity at lower costs, making products cheaper and distorting prices. All these make it harder for agroecological farmers to compete. The intensive lobby of large corporations also supports a legal and economic framework in favour of industrialised agriculture.

Only a few public, bilateral donors and international organisations – France, Switzerland, Germany, the FAO and International Fund For Agricultural Development – specifically identify agroecology as a sustainable approach for achieving food security. Most donors endorse some principles of agroecology but in practice direct funding towards reinforcing and tweaking conventional agriculture methods, effectively locking out funding for agroecology. For example, 85% of projects funded by the Gates Foundation were for industrial agriculture and increasing its efficiency (e.g. improving pesticide practices or livestock vaccines). Agroecology is often reduced to the ecological dimension, with donors paying less attention to concerns like the circular economy or co-creation of knowledge with farmers and local communities. Furthermore, lack of finance plus insecure land tenure tend to discourage poor farmers to take up agroecology. Taken together, these obstacles reinforce the economic and political power currently held within the agro-food industry.

Long-term action is needed to scale up agroecology. Suggestions by FAO and experts include:

Wider stakeholder involvement. Civil society organisations (CSO) and research institutions could work with policymakers and farmers to provide technical expertise in support of agroecology. NGOs, for example, can also support efforts of agroecological farmers, farmer networks and organisations through collaboration with researchers to disseminate information among sceptical farmers on the benefits of agroecological farming and its increased resilience, including its economic profitability. CSO’s could also influence donors, policymakers and the private sector to improve funding and support for policies that democratise agricultural and food governance. In general, the voices of farmers, indigenous and local communities need to be amplified in policy development and knowledge sharing.

Produced by researchers based on the meta-analyses: 1,2. These are a few of the most common examples. See studies for all.

References

| ↑1 | The literature is quite heterogeneous, with some studies focusing solely on agroecological farming systems and others on other systems that adopt agroecological principles, such as organic agriculture. In the briefing, we will include both types of studies as previous literature reviews: 1,2,3,4,5,6. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | his is one of the widest and systematic studies on agroecology. It included 286 projects in six regions of the world: Sub-Saharan Africa; Middle East and North Africa; Europe and Central Asia; South Asia; East Asia and Pacific; Latin America and Caribbean. See Table A2. |

| ↑3 | For example, average food production per household was up by 73% for 4.42 million small farmers growing cereals and roots. |

| ↑4 | A reanalysis of the previous studies. It included 114 agroecological organic projects. |

| ↑5 | Organic agriculture is included in literature reviews as a type of agroecological practice even though it is not as holistic as “agroecology”. |

| ↑6 | Hunger and malnutrition is not only a measure of food production, but of unequal access to food, inputs, markets, etc. |

| ↑7 | FAO conducted the widest literature review to date about agroecology potential in increasing climate resilience. The meta-analysis from 2020 consisted of peer-reviewed studies on agroecology (n=34 meta-analysis and 17 case studies selected out of 185). |

| ↑8 | Examples are: the use of organic fertilisers, higher crop diversity, agroforestry, biodiversification, soil management, and water harvesting. |

| ↑9 | Debray et al. (2019) focused on agropastoral land use in semiarid Africa and mixed-crop-livestock production in subhumid areas. |

| ↑10 | In Africa, agroforestry’s potential is high even in very dry grassland areas, as only 15% of farms currently have 30% tree cover. Across the continent, the practice of growing trees and crops in rotation can store 3,900 kg of carbon per year on average. Even in very dry, treeless parts of West Africa, like the Sahel, parklands can store 500 kg of carbon per hectare per year on average. |

| ↑11 | Based on the current evidence, their potential has been overestimated. The World Resources Institute took a deep dive into the science and found it is “unlikely to achieve large-scale emissions reductions.” This is because scientists are still learning about how much and for how long soils can store carbon. For example, unlike carbon in trees that tend to persist on its own, soil carbon is not something farmers can add to their soils once and leave alone. Sometimes carbon can escape and no study has accounted for this happening. For example, grazing livestock only sequesters carbon in certain settings and is made more likely alongside other factors – by and large, farms adopting agroecological practices in the US, Italy and England, and Wales had higher emissions because they required more land. |

| ↑12 | The literature is quite heterogeneous. There are many case studies that are judged agroecological by the authors while others analyse farms that strongly relate to agroecology or some of its key elements, but without referring explicitly to this term. |

| ↑13 | Subsidies have helped increase conventional farming productivity at lower costs, making products cheaper and distorting prices. All these make it harder for agroecological farmers to compete. |

Developing stringent rules for the global carbon market under A6.4 could set a precedent for high standards and restore faith…

A handful of countries are setting up 'nature markets' for trading biodiversity offsets, but the concept could lead to greater…